The Matewan Massacre, which occurred on May 19, 1920, was more than a shootout in a small West Virginia town. It was a powerful eruption of long-building tensions between coal miners seeking human dignity and coal operators determined to crush labor organizing. This event symbolizes the broader struggle between corporate power and working-class resistance in the Appalachian coalfields, a region shaped by economic exploitation and cultural resilience.

Understanding Matewan requires us to explore the entire coal company system, which included company towns, script wages, and the use of private mercenaries to intimidate and attack miners. This backdrop gave rise to enduring distrust—especially among Appalachian families—of coal companies, outside speculators, and any system that sought to enslave them through debt, dependency, or force.

Timeline of Key Events

- Late 1800s–Early 1900s: Speculators buy mineral rights and timber lands across Appalachia, often deceiving local landowners. Coal companies establish vast operations in West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and southwestern Pennsylvania.

- 1910s: Coal operators construct company towns and enforce payment in company script, trapping miners in economic dependency.

- Early 1920: The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) begins organizing miners in Mingo County, WV.

- May 19, 1920: The Matewan Massacre occurs when Baldwin-Felts agents attempt to evict union miners and are confronted by Police Chief Sid Hatfield.

- August 1, 1921: Sid Hatfield is assassinated on courthouse steps by Baldwin-Felts agents.

- Late 1921: The Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest labor uprising in American history, erupts as miners resist state and corporate repression.

Life in the Coalfields: Script Wages and the Company Town Trap

In the early 20th century, coal miners across Appalachia lived not in freedom, but in company towns—a system that blurred the line between employment and servitude. The coal companies didn’t just own the mines. They owned:

- Homes

- Stores

- Churches

- Schools

- Medical clinics

- And often, the police force and justice system

Miners were typically paid in script—a private currency issued by the company and only accepted at the company store, where prices were inflated. Miners had no access to competitive markets, and their wages barely covered food, clothing, or rent—let alone allowed them to save or relocate.

Debt to the company was often inevitable, making escape nearly impossible. This system—known as debt peonage—functioned as a form of economic slavery. It created a reality in which freedom of movement, freedom of speech, and freedom to organize were all suppressed.

The Baldwin-Felts Agents: Corporate Enforcers of Tyranny

When miners began organizing under the UMWA, coal companies responded with hired guns from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, a paramilitary firm notorious for violence and suppression.

These agents were known for:

- Spying on union meetings

- Beating or threatening organizers

- Conducting midnight raids

- Evicting families from company housing

- Using deadly force with impunity

The Baldwin-Felts agents acted above the law. Their methods were so extreme that Appalachian communities came to associate them with tyranny—outsiders armed not only with weapons but also with contempt for local people and values.

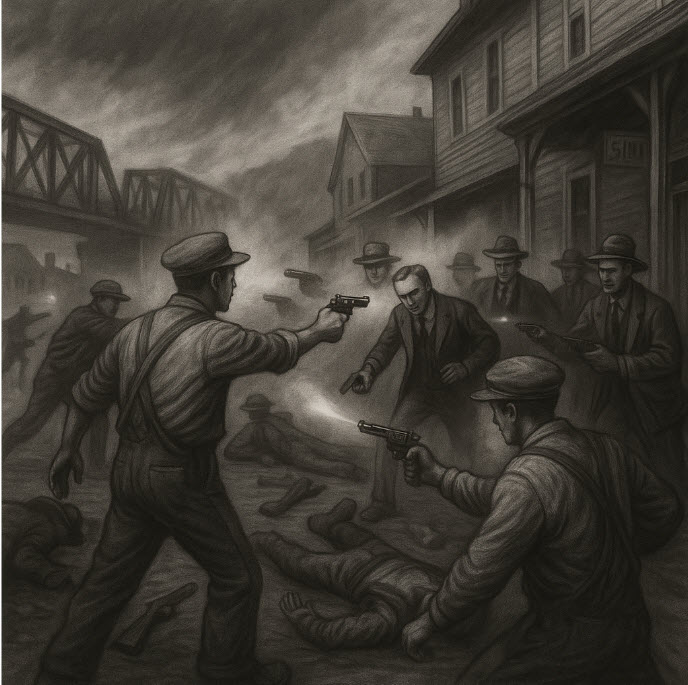

The Shootout in Matewan

On May 19, 1920, thirteen Baldwin-Felts agents arrived in Matewan, WV, to evict union miners. They were met by Police Chief Sid Hatfield, who, unlike many local lawmen, sided with the miners.

Hatfield, a former miner and native of the area, refused to allow the agents to carry out evictions without local court authority. A tense standoff at the Matewan train depot escalated into a gunfight. The resulting battle left:

- 7 Baldwin-Felts agents dead, including Albert and Lee Felts

- 2 miners dead

- Mayor C.C. Testerman fatally wounded

The Matewan Massacre, as it came to be known, was a rare victory for the miners. But it also intensified the coal companies’ resolve to crush the union movement. One year later, Baldwin-Felts agents assassinated Hatfield on courthouse steps in Welch, WV—a chilling reminder of who held power.

Exploitation of Appalachia: Land, Timber, and People

The fight over coal was part of a larger pattern of outsider exploitation in Appalachia that stretched back to the late 19th century:

1. Confiscation of Land and Resources

Speculators, lawyers, and timber companies traveled through the mountains of eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, and western Virginia, purchasing mineral rights and timber lands from poor, often illiterate Appalachian families—sometimes using deceptive contracts or verbal promises.

Once rights were secured, companies stripped the mountains of their forests, using the wood to build mine shafts, railroad trestles, and company housing. Clear-cutting destroyed wildlife habitats, caused erosion, and devastated the land that once supported subsistence farming and hunting.

2. Loss of Self-Sufficiency

Before the coal boom, Appalachian families were proud, self-sufficient people—deeply tied to the land and their heritage. The arrival of coal companies changed that. Within a generation, many Appalachian men became wage laborers dependent on a single industry controlled by absentee corporate interests.

Long-Term Distrust and Cultural Memory

The brutality and manipulation employed by coal companies—especially through agents like the Baldwin-Felts—left deep scars in Appalachian communities, scars that have not healed even today.

West Virginia

In Mingo and Logan counties, memories of Hatfield’s murder, the Battle of Blair Mountain, and the company store system became part of the oral tradition. Coal companies were seen as occupying forces, and even now, many West Virginians speak with distrust about “the people who run things from outside.”

Eastern Kentucky

In counties like Harlan and Perry, similar uprisings and violent labor disputes took place. The region earned the nickname “Bloody Harlan” during the 1930s due to multiple deadly strikes. Here too, coal companies used thugs, spies, and violence to stop unionization. The resentment was so deep that entire communities distrusted any outsider—even government agents—as likely being aligned with the coal bosses.

Pennsylvania

In the anthracite coal regions of northeastern Pennsylvania, the cultural makeup differed somewhat—being more heavily populated by Irish, Polish, Slovak, and Italian immigrants. Nevertheless, the same dynamic existed: company control, script payments, dangerous work, and violent suppression of organizing. Strikes like the Lattimer Massacre (1897) and violent confrontations throughout the 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike laid the foundation for similar mistrust.

A Shared Cultural Outlook

Though the ethnic makeup of Pennsylvania miners differed from the Scots-Irish and English Protestant roots of many southern Appalachian communities, both regions developed a deep-seated opposition to corporate control, especially when enforced through violence. Among southern Appalachians, this opposition was also fused with clan loyalty, oral storytelling, and religious ethics, making betrayal and exploitation nearly unforgettable offenses.

Appalachians do not forget injustice. In the coalfields, history is not just remembered—it’s inherited.

Similar Violent Strikes in the Early 1900s

The Matewan Massacre was one of many violent labor confrontations in the early 20th century. Here are other key examples:

| Event | Date | Location | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattimer Massacre | 1897 | Lattimer, PA | Sheriff’s deputies killed 19 unarmed immigrant coal miners during a peaceful march for better wages. |

| Paint Creek–Cabin Creek Strike | 1912–1913 | WV | Striking miners fought coal company guards and state troops. Machine guns and armored trains were used against workers. |

| Ludlow Massacre | 1914 | Ludlow, CO | Colorado National Guard and company guards attacked a tent colony of striking miners, killing at least 19 people, including women and children. |

| Steel Strike of 1919 | 1919 | Nationwide | Massive strike involving over 350,000 steelworkers, met with employer violence, arrests, and federal pressure. |

| Battle of Blair Mountain | 1921 | WV | 10,000 armed miners marched against coal operators and government forces in the largest labor uprising in U.S. history. |

| Harlan County Wars | 1931–1939 | KY | A series of deadly labor conflicts, including shootings and assassinations, in the coalfields of eastern Kentucky. |

Conclusion

The Matewan Massacre was not an isolated incident—it was the spark in a powder keg of corporate exploitation, cultural pride, and suppressed outrage. In the hills of West Virginia, and across Appalachia, generations of miners and their families endured economic bondage, physical abuse, and cultural erasure at the hands of coal operators and their hired enforcers.

But the people of these mountains—especially those in West Virginia, Kentucky, and parts of Pennsylvania—refused to forget. They told their stories, raised their children on tales of Sid Hatfield, Frank Keeney, and the coal company wars, and passed down a fierce independence that would shape regional politics, religion, and labor movements for a century.

Matewan is not just a story of labor versus capital. It is the story of Appalachian dignity versus outside control, a story that still echoes in the hills to this day.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

The 1987 movie “Maitwan” with Chris Cooper and James Earl Jones is a fictionalized account of the Maitwan Massacre. Some artistic license has been taken with the events, but it is still accurate in terms of an example of labor strife in the Appalachian mining community.

This documentary discusses the events of Maitwan from a historical perspective. There is a question concerning which side fired the first shot.

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

I think the content is worthwhile, but it may contain opinions or language I don’t agree with.

Realize that I sometimes use phrases like “trans man”, “trans woman”, “transgender” or similar language for ease of communication. Obviously, as a conservative Christian, I don’t believe anyone has ever become the opposite sex.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.