There are few names in history that generate as much ideological fervor—or controversy—as Karl Marx. He is hailed as a liberator by some, vilified as a destroyer by others. For over a century, Marx’s ideas have catalyzed revolutions, toppled governments, and redefined economics and politics around the globe. But what kind of man was Karl Marx? What were the roots of his thought? What shaped his doctrines, and what do they reveal about the modern movements that trace their lineage to him?

In The Devil and Karl Marx, historian Paul Kengor steps beyond economic theory and dives into the moral and spiritual dimensions of Marx’s life, writings, and legacy. The book is as much an investigation of Marx the man as it is an exposé of the deadly fruit his ideas bore. Far from a dry academic treatment, Kengor’s work reads like a layered biography and theological critique. It is scholarly, yet accessible—perfect for the motivated student seeking to understand the ideological and moral foundations of Marxism and Neo-Marxism.

About the Author: Paul Kengor

Dr. Paul Kengor is a professor of political science at Grove City College in Pennsylvania, a conservative Christian institution known for its commitment to classical liberal arts education. With a Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh and advanced studies in political theory and history, Kengor has long specialized in topics at the intersection of ideology, faith, and public policy. His earlier books include God and Ronald Reagan, The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of Communism, Dupes, and Takedown: From Communists to Progressives, How the Left Has Sabotaged Family and Marriage.

As a Catholic and a cultural conservative, Kengor is deeply invested in evaluating the spiritual and cultural consequences of political ideologies. His background uniquely equips him to critique Marxism not just on economic or political grounds, but on moral and theological ones. It’s not surprising that someone so familiar with Cold War history and the ideological threats to Western civilization would eventually turn his attention to Marx—the man whose theories gave birth to communism and all its radical offshoots.

Why This Book? What Prompted Kengor’s Authorship?

Kengor’s motivation for writing The Devil and Karl Marx is rooted in two primary concerns: the historical legacy of Marxism and the alarming resurgence of Marxist rhetoric and tactics under new names—especially within academia, progressive politics, and cultural institutions.

In recent years, terms like “cultural Marxism,” “Neo-Marxism,” and “critical theory” have gained traction, sometimes dismissed as scare-terms by progressives, but increasingly vindicated by the explicit statements of modern activists themselves. The Black Lives Matter movement, for example, was co-founded by self-described “trained Marxists.” College campuses frequently elevate thinkers influenced by Marxist ideology under the banners of social justice, equity, and decolonization.

Kengor sensed that the time was ripe to revisit the roots. But rather than merely critiquing Marxism as a theory, he sought to explore the life and character of the man behind it. After all, ideas are never divorced from the people who articulate them. Who Marx was, how he lived, what he believed, and whom he hated—these things matter if we are to understand the full scope of the ideology he birthed. And the evidence, as Kengor demonstrates in painful detail, is dark.

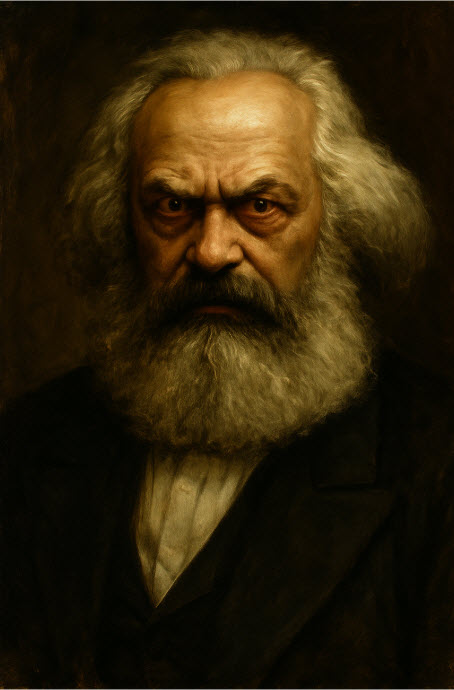

Karl Marx: A Life Marked by Conflict and Contempt

Kengor’s portrait of Karl Marx is not flattering. Born in 1818 in Trier, Germany, Marx was the son of a Jewish lawyer who converted to Lutheranism—largely to keep his legal practice under Prussian restrictions. Marx, however, abandoned all religious affiliation early in life and became a bitter critic not only of Christianity but of religion itself. He famously referred to religion as the opium of the people, but Kengor shows that his disdain ran far deeper than intellectual disagreement—it bordered on spiritual rebellion.

From his student days, Marx was combative, arrogant, and dismissive of those he deemed intellectually inferior. He was expelled from universities and lost publishing opportunities due to his aggressive tone and volatile personality. While he cultivated a persona as a man of the people, Marx was utterly dependent on financial support from others—chiefly his wealthy collaborator Friedrich Engels, who subsidized Marx’s lifestyle while also underwriting the early socialist movement.

But what emerges most clearly from Kengor’s account is that Marx was not simply a secular reformer. He was a man driven by hatred: hatred of God, hatred of the bourgeoisie, hatred of capitalism, and—perhaps most disturbingly—hatred of mankind itself.

Marx’s Hatred of Christianity and the Spiritual Dimension

Kengor draws heavily from Marx’s own poems, letters, and unpublished manuscripts—materials largely ignored by academic Marxists but indispensable for anyone wishing to understand the soul of the man. These writings, especially his early poetry, are disturbingly dark.

In one poem, Marx writes:

“Thus heaven I’ve forfeited, I know it full well.

My soul, once true to God, is chosen for Hell.”

In another piece, he appears to fantasize about making a pact with the devil. And in yet another, he describes the destruction of the world as a personal ambition:

“Then I will be able to walk triumphantly,

Like a god, through the ruins of their kingdom.”

Kengor stops short of accusing Marx of literal Satanism, but he does not shy away from pointing out the spiritual rot at the core of Marx’s worldview. The hatred for religion wasn’t merely philosophical—it was visceral. Marx wanted to see not only religion but religious people crushed. He didn’t just believe in the abolition of religion; he exulted in the idea of destroying it.

A Gaze from the Abyss: Eyewitness Impressions of Marx’s Unsettling Presence

While many critics have focused on Karl Marx’s writings and ideological impact, some of the most chilling accounts in Paul Kengor’s The Devil and Karl Marx come not from theoretical critiques but from those who met Marx personally—and walked away disturbed.

One such anecdote, often cited and chilling in its detail, involves visitors to Marx’s home in London who reported encountering Marx peering through a window or sitting at his desk, with an expression described as “beady,” “piercing,” and—most hauntingly—“demonic.” His eyes, deeply set and intense, gave the impression of something not merely human. His stare reportedly unsettled visitors, leaving them with a sense of spiritual discomfort more than intellectual unease.

Kengor draws from several sources, including family friends, journalists, and fellow revolutionaries like Wilhelm Liebknecht, to sketch Marx not just as an angry theorist but as a man cloaked in emotional volatility and spiritual gloom. His study was filled with cigarette smoke, his desk often buried under manuscripts, and he would spend days in a near-trance—muttering to himself, pacing, or sitting motionless. According to Liebknecht, Marx’s moments of conversation could quickly turn into volcanic outbursts of rage, often directed at even his closest allies.

To many observers, Marx seemed possessed by his ideas—consumed by them in a way that robbed him of human warmth. His daughter Eleanor once admitted that she and her sisters approached their father with fear, never knowing when he would lash out. His housekeeper Helene, with whom he fathered an illegitimate child, endured his moody dominance for decades in near silence.

In one particularly memorable retelling, a visitor described approaching Marx’s house and seeing him at the window, staring blankly down the street. His eyes seemed to follow the person with a kind of cold calculation—neither curious nor welcoming, but alien. The impression left was not of brilliance, but of a kind of spiritual vacancy. One is reminded of the line from Marx’s own poem, The Player, in which he writes:

“See this sword?

The prince of darkness sold it to me.”

Whether such lines were mere literary dramatics or confessions of something deeper, Kengor’s account leaves little doubt that Marx was not merely a theorist of revolution—he was a man animated by disdain, unrest, and, quite possibly, something darker.

Sexual Misadventures and Family Disgrace

Far from the image of a noble revolutionary devoted to the proletariat, Karl Marx was deeply selfish in his personal life. He fathered an illegitimate son with his family’s longtime maid, Helene Demuth, then refused to acknowledge the child. Responsibility for the boy was pawned off on Engels, who falsely claimed paternity to protect Marx’s reputation.

Marx never lifted a finger to support the child or offer him affection. The young man, Freddy, grew up in obscurity and poverty—a walking contradiction to Marx’s proclaimed concern for the downtrodden. Kengor uses this episode to underscore a crucial point: Marxism’s theoretical compassion rarely extends to personal practice.

Marx also made no effort to improve the lives of his wife and children, despite numerous opportunities. He spent family inheritances irresponsibly, failed to provide for them adequately, and frequently neglected them emotionally and physically. His wife Jenny von Westphalen bore the brunt of Marx’s recklessness, watching their children die one by one in squalid conditions while her husband wrote treatises on equality.

A Trail of Tragedy: Death, Despair, and Dysfunction in the Marx Household

Three of Marx’s children died in infancy, largely due to the unstable, unsanitary conditions the family endured. His refusal to work a stable job left the family destitute even when friends offered help. At times, the Marx household lacked food, heat, and basic necessities. Meanwhile, Marx remained intellectually aloof, consumed by ideology, with little thought to practical care.

Those daughters who lived into adulthood were emotionally burdened by their father’s ideological legacy and dysfunctional behavior. Jenny Caroline, his eldest, died of cancer. Laura and Eleanor became ardent Marxists themselves—each marrying revolutionaries, and each eventually taking her own life. Laura died in a suicide pact with her husband, Paul Lafargue. Eleanor followed suit after her manipulative lover Edward Aveling betrayed her.

The pattern is tragic and revealing: the Marx family was emotionally cold, spiritually hollow, and ideologically poisoned. Kengor makes a compelling case that this was not coincidental, but consistent with the worldview of its patriarch—a man whose life bore the fruits of bitterness, not liberation.

Financial Parasitism and Cold Indifference to Inheritance

Marx’s financial irresponsibility is a recurring theme in the book. He viewed money as a means of entitlement, not stewardship. Engels supported Marx and his family for decades, paying for everything from rent to burial expenses. Instead of gratitude, Marx expressed resentment when Engels couldn’t give more.

More distastefully, Marx treated family deaths with shocking callousness—especially when they involved an inheritance. He made wry, morbid remarks about when certain relatives might die so that he could collect money. In one letter, Marx referred to the death of his uncle as “fortunate” because it provided some much-needed funds. This opportunism paints a portrait not of a man burdened by poverty, but embittered by entitlement.

Suicide Pacts and Ideological Fanaticism

Kengor devotes substantial attention to the deaths of Marx’s daughters—particularly Eleanor Marx. She had devoted her life to promoting her father’s ideology, but it brought her neither joy nor stability. Her relationship with Edward Aveling, an atheist and a known womanizer, ended in despair. Deeply disillusioned but ideologically committed, Eleanor took her own life.

The same pattern played out with Laura and her husband Paul Lafargue. Before committing suicide, Lafargue wrote that he no longer had the strength to contribute to the revolution, and therefore believed it was right to die. It was not illness or depression that drove them—but ideology. They died in service to the very Marxism that had deformed their lives.

Kengor’s point is devastating: Marxism, when taken seriously, does not produce life. It consumes. It promises utopia but demands sacrifice—of logic, of family, of faith, and often of life itself.

Marxism as a Mirror of the Man

Having explored Marx’s life, Kengor returns to his central thesis: Marxism is not merely flawed theory—it is the embodiment of a deeply flawed man. Marx’s ideology was born of hatred—hatred for religion, tradition, free enterprise, and ultimately for humanity itself.

Where Marx despised the family, Marxism attacks the family. Where Marx mocked gratitude, Marxism encourages grievance. Where Marx harbored racial prejudice, Marxism today stokes racial division under the guise of justice. Where Marx refused responsibility, Marxism shifts all blame onto systems and structures.

In other words, Marxism reflects Marx. The darkness in his soul found a political outlet. Kengor argues that Marxism’s fruit in history—gulags, mass starvation, censorship, persecution—is not a corruption of Marx’s vision but the natural outcome of it.

From Marx to Neo-Marxism: The Ideological Lineage

Kengor carefully traces the evolution of Marx’s ideas through the 20th century into today’s cultural Neo-Marxism. Where classical Marxism failed to produce global revolution through economics, later thinkers like Antonio Gramsci, Herbert Marcuse, and members of the Frankfurt School adapted Marx’s methods to culture.

They realized that the path to revolution was not through the factory, but through the university, the media, and the arts. Cultural Marxism targeted morality, family, gender, religion, and national identity as the oppressive structures that needed dismantling.

Today, terms like “equity,” “social justice,” “critical theory,” and “intersectionality” are used in place of Marx’s “class struggle,” but the structure is the same: divide people into oppressor and oppressed, eliminate traditional moral frameworks, and replace them with a revolutionary vision of man-made justice.

Kengor’s warning is urgent: we are not beyond Marxism. It has simply morphed. Neo-Marxism, especially in the West, now disguises itself as compassion while preserving its core: resentment, deconstruction, and ultimately, tyranny.

Major Principles of Marx’s Life According to Kengor

Throughout the book, several dominant traits of Marx’s life emerge, each mirrored in the ideology he spawned:

- Hatred of God – Marx’s atheism was not neutral, but active and aggressive.

- Desire for Destruction – Marx saw revolution not as reform, but as annihilation of existing order.

- Moral Hypocrisy – While preaching equality, Marx lived irresponsibly and selfishly.

- Racial Prejudice – Marx’s private writings are filled with ethnic slurs and elitist contempt.

- Misogyny and Sexual Exploitation – He used women and denied responsibility for his own child.

- Parasitism – He lived off others’ wealth while condemning capitalism.

- Spiritual Darkness – His own words, actions, and demeanor radiated bitterness and unrest.

- Death Cult Legacy – Marx’s family and ideological heirs embraced death as an acceptable cost of revolution.

Final Reflections: Why This Book Matters

The Devil and Karl Marx is not just a biography or an ideological critique—it is a moral and spiritual reckoning. It warns readers not to separate ideas from the character of the men who propagate them. Kengor’s research shows that the horrors of communism didn’t come out of nowhere—they sprang from the very mind and soul of Karl Marx.

For Christians and cultural conservatives, the book provides a sobering reminder that evil ideas often present themselves as liberating. Marxism is a false gospel—one that offers justice without God, purpose without repentance, and salvation through destruction.

As America and the West flirt with Neo-Marxist language and policy, we would do well to look again at the man behind the movement. If the tree is known by its fruit, Marxism is rotten at the root.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

MMXXV

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

If I have listed the content, I think it is worthwhile viewing to educate yourself on the topic, but it may contain coarse language or some opinions I don’t agree with.

Realize that I sometimes use phrases like “trans man”, “trans woman”, “transgender” , “transition” or similar language for ease of communication. Obviously, as a conservative Christian, I don’t believe anyone has ever become the opposite sex. Unfortunately, we are forced to adopt the language of the left to discuss some topics without engaging in lengthy qualifying statements that make conversations awkward.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.