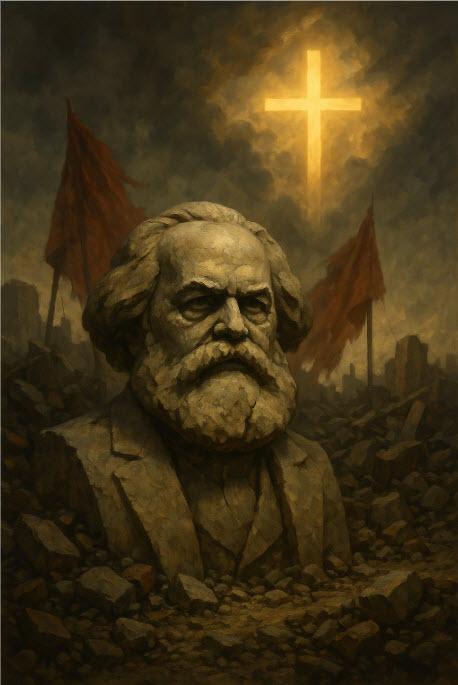

Few texts in modern history have generated more controversy—or inspired more movements—than The Communist Manifesto, penned by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848. At just under 25 pages in most English translations, this slim document is anything but minor in its impact. It has shaped revolutions, toppled monarchies, reconfigured political economies, and left an indelible mark on the 19th, 20th, and now 21st centuries. And though the Iron Curtain has fallen and the Berlin Wall lies in rubble, Marx’s vision—radical, utopian, and profoundly critical—remains a philosophical skeleton in the closet of many ideologies that still seek to remake the world in his image.

The Communist Manifesto is not a dispassionate policy proposal. It is a call to arms. Its famous opening—“A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism”—serves as both a warning and a rallying cry. Marx understood himself as a prophet of social upheaval and class liberation. But beneath the inciting rhetoric lies a profound worldview—a secular eschatology built not on grace, but on class struggle; not on redemption, but on revolution. It is that worldview, and the man who conjured it, that deserves our serious and critical attention.

Who Was Karl Marx? A Brief Biography

Karl Heinrich Marx was born on May 5, 1818, in Trier, a town in the western German Rhineland. He was the third of nine children born to Heinrich and Henriette Marx. His father, a lawyer of Jewish descent, converted to Lutheranism just prior to Karl’s birth—likely a pragmatic move to keep his legal career afloat in a society that restricted Jewish participation in civic life. Thus, Marx was baptized in the Christian faith but raised in a home of nominal religiosity and increasingly secular philosophy.

Young Marx was a bright student, showing early aptitude for literature, law, and philosophy. He studied at the University of Bonn and later the University of Berlin, where he was drawn to the radical ideas of the Young Hegelians—a group that reinterpreted the philosophy of G.W.F. Hegel in revolutionary and often atheistic directions. It was during these formative years that Marx fully abandoned religious belief and began cultivating a materialist worldview. His doctoral thesis was on the Greek atomists—Democritus and Epicurus—revealing early interest in materialist philosophy and the idea that history was driven by impersonal, economic forces.

In 1843, Marx married Jenny von Westphalen, a woman of noble descent. Together, they would have seven children, though only three survived to adulthood. Marx struggled to support his family and was often reliant on the financial support of his friend and co-author Friedrich Engels, the son of a wealthy German industrialist.

Exiled from Germany due to his radical writings, Marx lived in Paris, Brussels, and finally London, where he would spend the remainder of his life in relative poverty and obscurity, working tirelessly on his magnum opus, Das Kapital. He died in London in 1883. At his funeral, Engels remarked that Marx was “the best hated and most calumniated man of his time,” but predicted his ideas would outlive him. They certainly have.

Marx’s Character and Disposition

Marx was by many accounts a difficult man—brilliant, but caustic; affectionate to friends, but ruthless to opponents. His correspondence is filled with insults, polemics, and seething hatred toward those who opposed his ideas. He was doggedly committed to his cause, willing to suffer hardship for his intellectual and revolutionary convictions. But he also alienated many allies, and his radicalism often burned bridges even within leftist circles.

Philosophically, Marx was a historicist and materialist. He rejected the idea of universal moral truths or divine revelation. For him, man was a product of his material environment, not a being created in the image of God. Sin, in Marx’s framework, is not rebellion against a holy Creator but the result of unjust economic structures.

Historical and Ideological Context of The Communist Manifesto

To understand The Communist Manifesto, one must step into the churning world of mid-19th century Europe. The year 1848 was revolutionary in the most literal sense. A wave of political and social uprisings swept across the continent—France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire were all rocked by calls for greater liberty, democracy, and the overthrow of aristocratic privilege. Though most of these revolutions failed, they exposed the deep unrest among the working class and the waning power of monarchic regimes.

The industrial revolution had transformed Europe’s economy. Cities swelled with factory workers, many of whom labored in squalid conditions for meager wages. Traditional agrarian life was eroding; social mobility was rare; the old nobility clung to their titles while the new bourgeoisie—the middle-class business owners—rose in wealth and influence. Yet the proletariat, the industrial working class, often bore the cost of this transformation without sharing in its rewards.

Into this volatile environment, Marx and Engels published their manifesto. Commissioned by the Communist League—a small association of radical workers—the document was designed to clarify the aims of communists and to rally the working class to revolutionary action. Its timing was fortuitous: 1848’s revolutions provided the very stage Marx had hoped for. Though they failed, the ideas they unleashed did not.

The manifesto is structured into four main sections:

Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties – A political strategy statement

Bourgeois and Proletarians – A sweeping historical narrative of class struggle and the rise of the bourgeoisie

Proletarians and Communists – A defense of communism and rebuttals to common criticisms

Socialist and Communist Literature – A critique of competing socialist ideologies

The Central Drama: History as Class Warfare

One of the most defining features of Marx’s worldview is his commitment to historical materialism—a way of interpreting history not as a series of moral decisions, providential movements, or cultural evolutions, but as a cold, mechanistic conflict between classes.

In the famous opening section, Bourgeois and Proletarians, Marx asserts:

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

This claim is totalizing. Marx is not merely saying that class struggle is a recurring theme in human history; he insists that it is the defining engine of all societal development. From slave versus master in ancient society, to lord versus serf in feudal society, to bourgeois versus proletarian in capitalist society—history, to Marx, is a relentless dialectic of oppression and revolt.

This interpretation draws heavily from the Hegelian dialectic, wherein progress occurs through conflict between opposing forces (thesis vs. antithesis) that eventually produce a new synthesis. Marx secularized this concept, stripping it of Hegel’s idealism and recasting it in material terms. In Marx’s scheme:

- The bourgeoisie (capital-owning class) represents the current dominant thesis

- The proletariat (working class) is the revolutionary antithesis

- Their violent conflict will produce a classless, communist society—the final synthesis

This framework became the beating heart of Marxist ideology and remains embedded in modern Neo-Marxist thought, where class is often substituted with categories like race, gender, or sexuality. But in its original form, it was the proletarian struggle that held center stage.

The Rise of the Bourgeoisie and the Glories of Capitalism (Backhanded Praise)

Marx’s analysis of the bourgeoisie is more nuanced than it might first appear. In one of the manifesto’s more surprising turns, Marx actually praises the transformative power of capitalism—at least in a backhanded way.

He credits the bourgeoisie with revolutionizing society:

The bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most revolutionary part.

Marx recognizes that capitalism broke the feudal system, ushered in industrialization, expanded global markets, and transformed the material conditions of life at an unprecedented rate. Factories, railroads, and trade networks—all these sprang from the innovations of the capitalist class. The system’s creative destruction swept away medieval stagnation and unleashed productive forces never before seen.

Yet this praise is swiftly followed by condemnation. Capitalism’s dynamism, Marx argues, carries within it the seeds of its own destruction. The bourgeoisie, by exploiting the proletariat, has created the very class that will one day overthrow it. The system is inherently unstable, driven by crises of overproduction, inequality, and immiseration.

It is worth pausing here to note the strategic brilliance of Marx’s rhetoric. He uses capitalism’s own triumphs against it. The logic is this: yes, capitalism accomplished much—but now it must be discarded, for it has fulfilled its historical role and revealed its internal contradictions.

This rhetorical sleight of hand continues throughout the manifesto.

The Heart of the Matter: The Abolition of Private Property

Nothing in the manifesto has stirred more controversy—or inspired more revolutionaries—than Marx’s call to abolish private property. This is not a marginal suggestion. It is the very soul of the communist program.

The theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property.

To be clear, Marx is not referring to personal belongings like shoes, toothbrushes, or your grandmother’s china cabinet. He is speaking specifically about capital—productive property, such as factories, farms, machines, and means of production. He wants to eliminate the class distinction between owners and workers by eliminating ownership itself.

Marx claims that property is the root of class domination. If the bourgeoisie owns the factories and tools, then the proletariat must sell its labor to survive. This, to Marx, is inherently exploitative—what he calls wage slavery. The only just solution is to transfer ownership to “the community”—that is, the state acting in the name of the people.

This is no mere economic proposal. It is a worldview. Marx envisions a society in which:

- Classes no longer exist

- The state eventually withers away

- Each person contributes “according to his ability” and receives “according to his needs”

- Traditional family, religion, and nationalism dissolve

This utopia is what Marx calls “communism.” But to get there, a violent revolution is necessary.

Marx’s Ten-Point Plan

To transition from capitalism to communism, Marx offers a ten-point program—practical steps for dismantling bourgeois power. Some of these proposals have since become normalized in various Western societies, though often stripped of their revolutionary origins. These include:

- Abolition of property in land

- Heavy progressive or graduated income tax

- Abolition of inheritance rights

- Confiscation of property of emigrants and rebels

- Centralization of credit in the hands of the state

- Centralization of communication and transport

- Extension of factories owned by the state

- Equal obligation to work

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries

- Free education for all children in public schools

Some modern commentators have noted how eerily familiar many of these items sound in 21st-century democracies. But it’s vital to remember that for Marx, these are not isolated reforms. They are steps toward the complete eradication of capitalism and the creation of a classless society.

A Christian Response to Marx’s Framework (Initial Reflections)

From a biblical standpoint, several profound problems emerge almost immediately in Marx’s analysis.

- Sin Is Not Primarily Economic

Marx sees man’s deepest problem as economic inequality and class oppression. But Scripture diagnoses a deeper illness: the human heart is deceitful above all things (Jeremiah 17:9). Sin cuts across all classes. The poor are not inherently virtuous, nor are the rich uniquely depraved. Both are sinners in need of redemption. Marx’s framework allows no place for original sin, individual responsibility, or repentance. - Private Property Is a Biblical Concept

The eighth commandment—You shall not steal—presupposes personal ownership. In Acts 5, Ananias and Sapphira are condemned not for refusing to share their land, but for lying about it; Peter tells them plainly that the property was theirs to do with as they wished (Acts 5:4). The communal generosity of the early church was voluntary, not coerced. Marx’s plan would mandate communalism through state force—an inversion of biblical charity. - Labor Has Dignity, Not Just Utility

Marx reduces labor to a function of economic production and class warfare. But Scripture portrays work as a dignified calling, instituted before the Fall (Genesis 2:15). Labor is not merely exploitation under capitalism; it is part of our image-bearing nature. - The Gospel Offers Hope; Marxism Offers Struggle

Marx offers no grace, no forgiveness, and no Savior. The only way forward is revolution. But Christ offers a better way—a transformation of hearts, not just structures; a kingdom not of this world, but one that redeems it nonetheless.

Marx’s Personal Outlook on Life

To understand the manifesto, one must first understand its architect. Karl Marx was not a detached academic surveying society from a distance. He was a man consumed with personal grievances, moral indignation, and ideological absolutism. Though brilliant, he was also bitter—toward religion, authority, the bourgeoisie, and even some of his allies.

Atheism as Foundation

Marx did not merely disbelieve in God; he detested the idea of God. His most famous remark on religion is well known:

Religion is the opiate of the masses.

Often misunderstood as simply a critique of comfort, Marx meant far more. He believed religion dulled the pain of the proletariat and kept them docile. He saw the church, especially the state churches of Europe, as complicit in bourgeois domination—upholding the status quo with sermons on patience and obedience.

But Marx went even further. He wrote in A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right:

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness.

In other words, Marx saw the eradication of religion as a necessary step in human liberation. For him, God was not a gracious Redeemer but a false idol constructed by the ruling class to control the poor. Religion, in this view, must be torn down along with the economic structures that sustain it.

This atheistic foundation shapes everything in the manifesto. Marx offers no transcendent moral law, no inherent dignity of the individual, and no hope beyond the revolution. He replaces God with history, sin with exploitation, and salvation with revolution.

Alienation and Bitterness

Marx was perpetually frustrated by his inability to rise within academic circles. After being exiled from Germany and banned from universities due to his radical views, he spent most of his adult life in poverty and illness, reliant on Engels for money. This personal marginalization fed his belief that he was a prophet rejected by the corrupt systems of his time.

His letters reveal a man with few real friends and many enemies. He often used bitter and dehumanizing language to describe those who opposed him—even fellow leftists. He once referred to Ferdinand Lassalle, a rival socialist, in deeply antisemitic terms, despite being of Jewish descent himself.

Such personal bitterness is mirrored in the tone of the manifesto. It is not merely analytical; it is combative. The language is incendiary, urgent, apocalyptic. Phrases like “overthrow of all existing social conditions” and “ruthless criticism of everything that exists” reflect Marx’s deep alienation from the world and his desire to reshape it by fire.

Revolutionary Purity

Marx believed in the necessity of violent revolution. Peaceful reform was for cowards or fools. He rejected the idea that the bourgeoisie could be reasoned with or reformed. They must be overthrown—period.

This radicalism set him apart even from other socialists of his day. Utopian socialists like Charles Fourier and Robert Owen envisioned communal living and harmonious societies. Marx derided them as naive. For Marx, the road to utopia ran through conflict, not consensus.

This belief in revolutionary purity—unchained by moral compromise—is a key feature of the manifesto. And it is one reason Marxism, in its various forms, has so often led to totalitarian outcomes. The revolution, once unleashed, demands purity at any cost.

The Neo-Marxist Legacy: From the Factory to the University

Though Marx did not live to see the Bolshevik Revolution, his ideas inspired countless movements—from the Soviet Union to Maoist China, from the Khmer Rouge to Castro’s Cuba. But his most enduring influence may be seen not in 20th-century revolutions, but in 21st-century ideologies. This is the realm of what many rightly call Neo-Marxism.

Neo-Marxism adapts the core of Marx’s theory—oppressor versus oppressed—but expands its categories beyond economics. Here are several of its key developments:

Antonio Gramsci and Cultural Hegemony

Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, imprisoned by Mussolini, asked why Marxist revolutions hadn’t taken hold in the West. His answer was simple: the cultural institutions—church, family, media, education—had created “hegemony,” a false consciousness that kept the proletariat in check.

Gramsci concluded that before any revolution could occur, these institutions must be infiltrated and subverted. This idea gave rise to the “long march through the institutions,” a phrase later popularized by German radical Rudi Dutschke. This strategy—still active today—focuses on changing a society’s cultural values before changing its economic system.

The Frankfurt School and Critical Theory

Building on Gramsci’s insights, the Frankfurt School (Herbert Marcuse, Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno) developed Critical Theory—a Neo-Marxist framework designed to critique all structures of Western society.

They replaced Marx’s economic determinism with a more flexible toolset that analyzed power dynamics in every area of life—race, gender, language, religion, family, and education. Critical Theory sees every hierarchy as suspect and every tradition as a potential mechanism of oppression.

Today, this line of thought has given rise to Critical Race Theory, gender ideology, and other expressions of intersectionality. These movements retain Marx’s key assumption: human beings are defined by their group identity, history is a tale of oppression, and liberation comes not through grace or transformation, but through political struggle.

The Rise of Identity Marxism

In modern progressive movements, economic class has been replaced or expanded by categories of race, gender, sexual orientation, and disability status. White, male, cisgender, Christian, able-bodied individuals are often cast as the “oppressor class,” while everyone else is placed within the ranks of the oppressed.

This updated Marxism no longer requires workers to unite. It only requires enough “marginalized” groups to form a coalition against the dominant cultural norms. It is Marx without the factory—repackaged for the university classroom and the activist street march.

A Christian Analysis of Marx’s Legacy

From the Christian lens—including thinkers like R.C. Sproul, Al Mohler, Paul Kengor and Voddie Baucham—several dangers stand out in both Marx and his successors:

The Denial of Individual Responsibility

Marx reduces people to group categories and historical roles. You are not first and foremost an image-bearer of God with personal moral agency—you are a member of a class, defined by your relationship to power. In Neo-Marxism, this becomes even more extreme: your moral worth is dictated by your group identity.

This contradicts biblical teaching. Scripture holds individuals accountable for their own sin (Ezekiel 18), calls for personal repentance (Acts 17:30), and levels the playing field at the foot of the Cross (Galatians 3:28).

The Rejection of Forgiveness and Reconciliation

Marxist and Neo-Marxist frameworks offer no real forgiveness—only perpetual struggle. The oppressor class can never be redeemed; they can only relinquish power. The oppressed can never forget; they must remember and resist.

But Christ teaches a better way. He tells us to forgive as we have been forgiven (Ephesians 4:32). The Cross allows both slave and master, Jew and Gentile, rich and poor to be reconciled in one body (Ephesians 2:14-16).

The Usurpation of God’s Justice

Marx seeks to bring justice on earth through revolution. But in doing so, he supplants God as the final Judge. He assumes perfect knowledge of history, guilt, and justice—but Scripture warns us that human justice is partial and fallible (Proverbs 21:2).

True justice is rooted in God’s unchanging character. It involves impartiality, truth, mercy, and righteousness. Marxism, by contrast, pursues justice through force and envy, without reference to God’s law or grace.

Are Marx’s Concerns Still Relevant?

We must begin with an honest assessment: not everything Marx said was entirely wrong.

If Marx were merely an economic journalist instead of a revolutionary ideologue, some of his observations would be considered astute critiques of early industrial capitalism. Indeed, parts of The Communist Manifesto read like a grim report from the slums of 19th-century London:

- Workers living in cramped tenements

- Twelve-hour factory shifts with no labor protections

- Children working beside their parents in dangerous conditions

- Massive wealth gaps between owners and laborers

These realities did exist, and many were morally indefensible. Marx saw them clearly and shouted into the void when others looked away. His error was not in identifying suffering, but in constructing a false gospel to remedy it.

The question for us is: do the same dynamics exist in 21st-century America?

Capitalism: Reformed or Repackaged?

There is no question that capitalism in the West has evolved since Marx’s day. Workers in America today enjoy labor protections, minimum wage laws, health benefits, and the ability to move between jobs. Unionization and workplace regulation have curbed many of the worst abuses of the 19th century. In these ways, Marx’s predictions have not held.

However, new forms of disparity have emerged. Consider the following:

- The wealthiest 10% of Americans control nearly 70% of the nation’s wealth.

- CEO pay has grown by over 1,000% since 1978, while worker wages have barely kept up with inflation.

- Large multinational corporations exert enormous influence over media, education, and politics.

- Many young workers face college debt, inflated housing prices, and stagnant wages—effectively indenturing them to the system.

So while the form of capitalism has changed, many of the power imbalances Marx described remain—albeit in modern packaging. A warehouse employee working under constant digital surveillance for a tech giant may not be a Dickensian chimney sweep, but he may still feel like a cog in a machine he cannot escape.

The New Bourgeoisie: Technocrats, Oligarchs, and Ideologues

Marx envisioned the bourgeoisie as factory owners and bankers. Today, the new elite wears a different face: Silicon Valley executives, ESG-compliant CEOs, global finance managers, and leftist university administrators. But the function remains: this class owns and controls the levers of production, culture, and information.

What’s changed is that today’s ruling class speaks in the language of “equity” and “inclusion” while outsourcing labor, censoring dissent, and manipulating social norms. Woke capitalism—what some call “stakeholder capitalism”—adopts the slogans of social justice while preserving its own power. It is, ironically, a fusion of Marxist rhetoric and capitalist structure.

This new class often:

- Determines which ideas are permissible in public discourse

- Partners with government agencies to suppress dissent (e.g., social media censorship)

- Uses ESG scores to pressure companies to adopt political agendas

- Advocates for policies that limit competition under the guise of global responsibility

In many ways, this ruling elite resembles the “managerial class” predicted by thinkers like James Burnham and Christopher Lasch. They do not own the means of production outright, but they control it bureaucratically.

Thus, while Marx misdiagnosed the cure, his identification of elites consolidating control was not entirely unfounded.

The New Proletariat: Gig Workers, Wage Slaves, and Cancel Targets

On the flip side, the modern “proletariat” may not be wearing overalls and carrying lunch pails, but they exist—just redefined.

- The gig economy has produced millions of workers with no benefits, no job security, and no upward mobility.

- Cancel culture and ideological litmus tests have made dissent dangerous, especially for conservative Christians.

- Many middle-class families find themselves priced out of housing, burdened by debt, and increasingly unable to save or retire.

- Small businesses are crushed under the weight of regulation and globalist policies that favor monopolies.

This is not classical proletarianism—but it is alienation and disempowerment. And in many cases, it’s the result not of free-market capitalism but of crony capitalism—where powerful corporations collude with government to rig the game.

This distinction is vital.

What Marx Got Wrong (Again)

While some of Marx’s observations ring true, his solutions remain fatally flawed:

- He blamed the system rather than the sin.

Capitalism does not create greed—it reveals it. Fallen man will exploit others under any system if left unchecked. - He ignored the dignity of voluntary exchange.

Capitalism, when properly restrained by moral law, allows for mutual benefit, generosity, and flourishing. It is not inherently exploitative. - He substituted envy for justice.

Marxist justice is rooted in resentment, not righteousness. It seeks to tear down rather than build up. As James 3:16 warns, “Where envy and selfish ambition exist, there is disorder and every vile practice.” - He offered revolution without redemption.

Marx promised utopia through bloodshed. But no system can fix man’s heart. Only Christ can bring true liberation—from sin, not merely from structures.

A Christian Way Forward

How, then, should Christians engage with the concerns Marx raised—poverty, exploitation, inequality—without falling into the errors of his ideology?

Affirm the Realities of Injustice

We should not be so afraid of Marxism that we deny real social sin. Scripture condemns unjust weights and measures (Proverbs 11:1), exploitation of the poor (Amos 8:4-6), and neglect of the needy (James 5:1-6). Christians should be the first to stand for righteous economic practices.

Champion Stewardship Over Envy

Private property is not a license for greed, but a responsibility for stewardship. The biblical model is not communism, but generosity—voluntary, cheerful, and rooted in love (2 Corinthians 9:7).

Defend the Image of God

Unlike Marx, Christians believe every person—regardless of class—is made in the image of God. This truth undercuts both elitism and class warfare. It calls us to treat each person with dignity, whether CEO or janitor.

Preach the Gospel, Not Utopia

Our ultimate hope is not in fixing economic systems, but in proclaiming a King whose kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). The church must not trade the gospel for political ideologies—right or left.

Summary of Key Takeaways

Let’s briefly retrace the major themes we’ve explored:

The Book: The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, is a revolutionary tract that seeks to ignite the proletariat to overthrow the bourgeois capitalist system. It is short, forceful, and filled with both passionate rhetoric and prescriptive ideology.

The Author: Karl Marx was a brilliant but embittered man, deeply anti-religious and committed to a materialist, class-centered view of history. His atheism, historicism, and revolutionary zeal shaped every part of his writing.

The Core Ideas:

- All of history is a story of class conflict

- The modern world is divided into bourgeois oppressors and proletarian victims

- Capitalism has been historically useful but is now destructive

- Private property must be abolished, along with traditional institutions

- Violent revolution is necessary to birth a new, classless society

The Consequences:

- Marx’s ideas led to 20th-century revolutions that killed over 100 million people

- His theory morphed into Neo-Marxism and Critical Theory in the West

- Modern identity politics draws from Marxist patterns of oppressor/oppressed

- Today’s elites use Marxist language to pursue capitalist ends—merging the worst of both worlds

The Christian Response:

- We affirm that injustice exists, but sin is deeper than economics

- We uphold the biblical dignity of work, property, and stewardship

- We believe in transformation through the gospel, not revolution

- We reject envy, class hatred, and utopianism as false gospels

The Legacy of The Communist Manifesto

Marx intended to change the world—and he did. His ideas lit a fuse under modern history, sparking revolutions, founding empires, and birthing totalitarian regimes. He has been both idolized and demonized, quoted and burned, canonized in universities and outlawed in dictatorships.

But even where communism has failed materially, Marx’s influence lingers ideologically. The language of equity, structural oppression, reeducation, and liberation theology carries echoes of his manifesto. So does the impulse to deconstruct all tradition, centralize power, and use state coercion to engineer moral outcomes.

Marx was wrong about many things—but he was right that ideas have consequences. His legacy stands as a solemn warning to Christians who flirt with utopianism or use secular tools to pursue sacred goals.

Glossary of Terms

- Alienation – The worker’s sense of being disconnected from the product of his labor, his own nature, and others

- Bourgeoisie – The capitalist class; owners of the means of production

- Class struggle – The central engine of historical change in Marx’s theory

- Communism – A stateless, classless society in which all property is owned collectively

- Critical Theory – A Marxist framework that critiques all social structures as tools of oppression

- Dialectic – A process of conflict and resolution that drives progress (from Hegel, adapted by Marx)

- Historical materialism – The belief that history is driven by economic forces, not ideas or morality

- Intersectionality – A Neo-Marxist concept that layers multiple identities (race, gender, sexuality) to measure oppression

- Neo-Marxism – Modern adaptation of Marx’s ideas applied to culture, race, gender, etc.

- Proletariat – The working class; laborers who sell their time for wages

- Revolution – The violent overthrow of one class by another; the means to achieve communism

Final Reflections: Truth and Hope

Karl Marx crafted a system that explained the brokenness of the world without reference to sin—and prescribed a solution that bypassed the Cross. He offered struggle instead of peace, revolution instead of repentance, utopia instead of the New Jerusalem.

To many, this was intoxicating. To others, deadly. But to Christians, it must be a cautionary tale.

Christians should never pretend that injustice doesn’t exist. But neither should we pretend that justice can be achieved apart from the just and righteous One. We should oppose oppression without embracing oppression’s inverse. We must resist exploitation without becoming revolutionaries who tear down the good along with the bad.

We are not saved by changing systems, but by being changed ourselves. The hope of the world is not Das Kapital, but the gospel. Not class war, but Christ crucified.

As Jesus said in John 8:32:

You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free.

And that truth is not a theory. It is a person.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

MMXXV

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

If I have listed the content, I think it is worthwhile viewing to educate yourself on the topic, but it may contain coarse language or some opinions I don’t agree with.

Realize that I sometimes use phrases like “trans man”, “trans woman”, “transgender” , “transition” or similar language for ease of communication. Obviously, as a conservative Christian, I don’t believe anyone has ever become the opposite sex. Unfortunately, we are forced to adopt the language of the left to discuss some topics without engaging in lengthy qualifying statements that make conversations awkward.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.