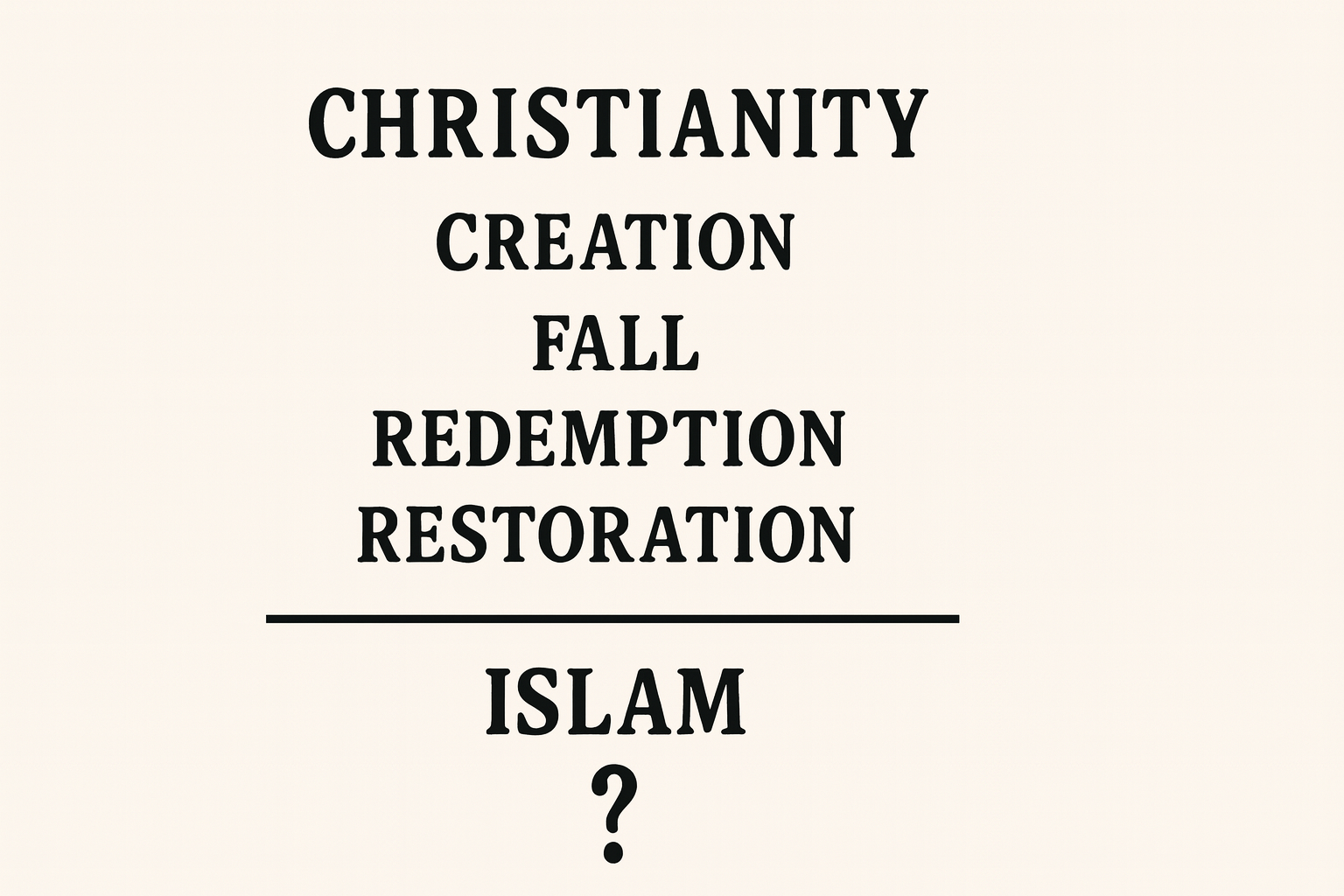

In a world increasingly torn between conflicting ideologies and religious claims, one question stands out as paramount: which worldview truly explains reality? Not merely in isolated doctrines or moral teachings, but in the grand scope of history—origin, meaning, morality, and destiny. For the Christian, the answer lies in the majestic sweep of redemptive history, a narrative beginning with Creation, broken by the Fall, redeemed through Christ, and consummated in Restoration. This is the story that binds the Bible’s sixty-six books into a unified whole. It is the story that makes sense of our world, our sin, our suffering, and our salvation.

By contrast, Islam—while claiming to be a continuation and completion of divine revelation—fails to offer such a coherent and redemptive metanarrative. Its view of God is unitarian and distant. Its vision of history is fragmented and moralistic. Its end goal is not a new heavens and new earth united with God, but a sensual paradise or eternal punishment determined largely by works. In short, it lacks the internal harmony and transformative hope that define Christianity.

This article will explore the difference between Christianity’s comprehensive redemptive story and Islam’s fragmented theological structure. We will draw from a variety of theologians and apologists—Nabeel Qureshi, James White, David Wood, John Frame, Greg Bahnsen, Francis Schaeffer, and Alister McGrath—who have engaged deeply with Islamic thought and worldview. We will also consider the historical and cultural factors that shaped Muhammad’s understanding of Judaism and Christianity, and why this likely contributed to the Qur’an’s theological fragmentation.

The Christian Metanarrative — Coherence from Beginning to End

At the heart of the Christian worldview is a seamless narrative arc:

- Creation — God created the world good, orderly, and purposeful. Humanity was made in God’s image to know and worship Him.

- Fall — Through sin, humanity rebelled against God, bringing death and disorder into the world.

- Redemption — God initiated a redemptive plan through the nation of Israel, culminating in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

- Restoration (Consummation) — God will restore all things through Christ’s return, culminating in a new creation where righteousness dwells.

This narrative answers the most fundamental questions of existence:

- Where did we come from?

- What went wrong?

- Is there any hope?

- Where is history going?

Francis Schaeffer argued that this kind of story is essential for meaning: “Christianity is not just a series of truths but Truth—Truth about all of reality.” Without such a framework, any worldview is reduced to fragments: unconnected facts, moral laws, or mystical experiences without explanatory power.

Islam’s Fragmented Theology and Historical Roots

Islam presents a starkly different picture. While it claims continuity with the Abrahamic tradition, the Qur’an offers no unified narrative structure comparable to the Bible’s grand arc. Instead, the Qur’an is a collection of episodic revelations, often delivered in response to immediate political or religious circumstances in Muhammad’s life. Its chronology is not linear, its theology is often contradictory, and its moral guidance is disconnected from a redemptive plan.

Why This Fragmentation?

One likely reason lies in the historical and theological context of Muhammad’s upbringing. Muhammad was born into a polytheistic culture in 6th-century Arabia, but he encountered both Christians and Jews through trade and dialogue. Yet these were not the biblically grounded Christians of Antioch or Jerusalem. Most scholars believe Muhammad interacted with Nestorian or Monophysite Christians, heretical sects that emphasized Christ’s divinity at the expense of His humanity (or vice versa), and which lacked a fully orthodox understanding of the Incarnation and Atonement.

Similarly, Muhammad’s exposure to Judaism was to a form that, while theologically rigorous, had no answer to the question of final redemption. With no Messiah, no cross, and no resurrection, Jewish eschatology remains—by its own admission—incomplete. The story ends in exile or legalism, not restoration.

Thus, Muhammad’s impression of the Judeo-Christian tradition was likely piecemeal, confused, and lacking Christ. From this partial exposure, he constructed a religious system that borrowed elements—monotheism, prophets, Scripture—but without the central character of the story: Jesus Christ, the Son of God.

Comparison Chart — Christianity vs. Islam

Here is a concise summary comparing the worldviews of Christianity and Islam:

| Apologetic Line | Christianity (Biblical View) | Islam (Critiqued View) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Encounter | Holy Spirit convicts, regenerates, and indwells | No indwelling or regenerating presence |

| Metanarrative | Creation → Fall → Redemption → Restoration | No coherent narrative, moralistic and episodic messages |

| Scriptural Unity | 66 books with unified theme of Christ | Qur’an lacks chronology, cohesion, or redemption arc |

| God’s Nature | Triune, loving, relational | Monadic, distant, unknowable |

| Salvation | By grace through faith, substitutionary atonement | Works-based, salvation never guaranteed |

| Purpose of History | Redemptive unfolding culminating in Christ | Predetermined fate, emphasis on obedience |

This chart draws from the insights of thinkers like James White and David Wood, who have consistently emphasized that Islam lacks both the theological depth and the narrative unity found in Christianity. For instance, White argues in What Every Christian Needs to Know About the Qur’an that “there is no overarching covenantal context in Islam. The Qur’an is simply not written to be read in any redemptive-historical way.”

Nabeel Qureshi and the Quest for Coherence

Few apologists embodied the journey from Islam to Christianity as personally and compellingly as Nabeel Qureshi. In his books Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus and No God but One: Allah or Jesus?, Qureshi shares not only the intellectual challenges he faced as a devout Muslim, but the spiritual dissonance he felt when Islam failed to provide a coherent, redemptive worldview.

One of the most striking aspects of Qureshi’s testimony is his emphasis on narrative. He writes:

Islam had given me a God who was distant, unknowable, and detached from human suffering. Christianity revealed a God who entered into suffering to redeem us.

This theological contrast is rooted in the difference in the metanarrative. In Islam, Qureshi notes, human history is not a redemptive journey but a proving ground for moral compliance. There is no “Fall” in the biblical sense, no understanding of sin as a nature inherited from Adam, and no Redeemer to bear sin away. As a result, there is no true restoration—only reward or punishment.

Qureshi came to see that Christianity’s story was not just more coherent; it was also more beautiful, more consistent with human longing, and more reflective of the moral and emotional weight of the world. He writes:

The gospel is not just good news because it promises heaven. It’s good news because it reveals a God who loves, who suffers, and who saves.

That beauty—rooted in coherence—was a central reason for his conversion.

Greg Bahnsen, John Frame, and the Foundation of Meaning

Where Qureshi approached the question experientially and theologically, Greg Bahnsen and John Frame approached it philosophically. As presuppositional apologists, both argued that only Christianity provides the necessary preconditions for intelligibility. That is, only the Christian worldview can account for logic, morality, meaning, and purpose.

Bahnsen’s Critique of Islam

While Bahnsen focused primarily on atheism, his arguments apply directly to Islam. He asserted that non-Christian worldviews are necessarily incoherent because they do not ground their beliefs in the triune, self-revealing God of Scripture. Islam, he would argue, posits a monadic God who cannot be both ultimate and personal, both transcendent and immanent. This Allah issues commands, but does not explain or embody them. The Qur’an demands submission, but offers no underlying logic for why God’s nature is good or why obedience is morally right.

Bahnsen wrote:

A worldview that cannot account for the laws of logic or the moral law ultimately refutes itself. It must borrow from Christianity to make sense.

Islam, in this view, is a borrowed system—it takes monotheism from Judaism, moral clarity from the Bible, and prophetic authority from the Christian tradition—but strips them of context, coherence, and Christ.

John Frame and the Self-Authenticating Word

John Frame, a Reformed theologian and philosopher, advances this point further by arguing that Scripture is self-authenticating—not because of a circular logic, but because of its divine authorship and internal coherence. He argues that Christians are justified in trusting the Bible because it alone speaks with the authority of the Creator, and it does so consistently from Genesis to Revelation.

Frame critiques the Qur’an on this very basis. Unlike the Bible, the Qur’an:

- Lacks progressive revelation (no development or fulfillment across history).

- Lacks covenantal structure (no binding relationship between God and His people).

- Lacks Christ-centered climax (no redemptive focal point).

Thus, Frame insists, it cannot interpret itself, cannot fulfill itself, and cannot justify its authority without appealing to external concepts it cannot support.

David Wood and the Moral Fragmentation of Islam

David Wood, an apologist with Acts 17 Apologetics, has taken a more direct and often confrontational approach. A former atheist turned Christian, Wood has debated dozens of Muslim scholars and has repeatedly pointed to the Qur’an’s internal contradictions and moral inconsistencies. His critique centers on how Islam’s theology produces fragmented ethics and an arbitrary sense of divine justice.

For example, Wood notes that in Islam, Allah forgives whom he wills and punishes whom he wills without a moral or judicial basis. There is no atonement—no cross, no payment, no substitution. This makes divine forgiveness appear arbitrary, not rooted in justice or holiness. Wood argues:

In Christianity, justice and mercy meet at the cross. In Islam, mercy comes at the expense of justice, or vice versa. There is no intersection.

This is not a minor oversight. It strikes at the core of Islamic theology. Without a substitutionary sacrifice, sin remains unresolved. Without resolution, restoration is impossible. Wood concludes that Islam is ultimately a religion of divine fiat, not divine faithfulness.

Furthermore, Islam’s moral vision—particularly regarding violence, polygamy, and the afterlife—lacks a cohesive rationale. The Qur’anic description of paradise is largely sensual and material. It bears little resemblance to the new creation of Revelation, where the redeemed dwell with God in perfect holiness.

Francis Schaeffer and the Need for Meaningful Narrative

Francis Schaeffer saw the loss of narrative in Western civilization as a descent into despair. In his view, every human being seeks coherence—a story that explains the world and gives meaning to life. When a worldview fails to offer this, people turn to existentialism, mysticism, or nihilism.

Schaeffer applied this critique not only to secularism but also to religions that fail to provide a full account of reality. Islam, in Schaeffer’s framework, is a religion of fragments: commands without context, stories without culmination, power without love. He wrote:

The Christian answer is not merely the best answer; it is the only answer that makes sense of the whole man in the whole world.

That includes reason, emotion, morality, and hope.

Alister McGrath and the Narrative Power of the Gospel

In his book Narrative Apologetics, Alister McGrath articulates a powerful point that resonates with the arguments of Schaeffer and Qureshi: human beings are not merely rational creatures—we are story-driven. We seek meaning not only in propositions but in patterns. Our deepest questions are not only answered in syllogisms but in stories.

McGrath argues that Christianity’s strength lies in its ability to tell a story that makes emotional, intellectual, and existential sense. Christianity speaks to the longings of the heart and the logic of the mind. It gives us a beginning, a tragic middle, a redemptive climax, and a hopeful conclusion.

The Christian faith tells a better story. A story that makes sense of who we are, what we see around us, and what we hope for.

By contrast, McGrath notes that other worldviews—including Islam—struggle to sustain a satisfying narrative. They may offer ethical principles or mystical experiences, but they cannot explain how the world got so broken or how it will be made right. Islam lacks a crucified and risen Savior, and thus lacks both atonement and resurrection—the twin engines of redemption and restoration.

For McGrath, Christianity’s narrative strength lies in its ability to integrate all of human experience—suffering, beauty, sin, hope, guilt, forgiveness—into a single, coherent story centered on Christ.

Theological Implications — Why Islam Must Fragment

If the Qur’an lacks coherence, and if Islamic theology fails to present a unified narrative, the question arises: Why? Why does Islam present a fragmented worldview?

Rejection of the Incarnation and the Cross

Islam’s central theological claim is Tawhid—the absolute oneness of God. From this premise flows its most decisive rejections:

- God cannot become man. Therefore, the Incarnation is blasphemy.

- God cannot die. Therefore, the Cross is a fabrication.

- God does not need mediation. Therefore, Jesus is not a Savior.

But by rejecting these truths, Islam cuts the thread of narrative continuity that binds the Bible together. From Genesis 3 onward, the Bible anticipates a Redeemer. The sacrificial system, the promises to Abraham and David, the prophetic declarations—all culminate in Jesus Christ. Remove Him, and the story collapses into disconnected rituals, legal demands, and prophetic warnings with no fulfillment.

Borrowed Elements Without Redemptive Center

Islam includes many familiar elements: Abraham, Moses, Jesus (as a prophet), divine revelation, final judgment. But these are not arranged around a redemptive core. They are moral exemplars, not types and shadows of a coming Messiah. Thus, Islam borrows the cast but rejects the plot. It reuses names but writes a different play.

As John Frame argues, this is what happens when revelation is severed from its covenantal and redemptive framework. The Qur’an, lacking an incarnate Redeemer and an atoning cross, becomes a book of commands rather than a book of redemption.

Judaism’s Incomplete Narrative

It is also instructive to compare Islam with Judaism, particularly post-Second Temple Judaism. While the Hebrew Scriptures provide the first three acts—Creation, Fall, and the beginning of Redemption through covenant—they stop short of the climax.

Judaism recognizes the problem of sin, the need for a Messiah, and the promise of restoration. But without Jesus, those threads remain unresolved. As Christians confess, Jesus is the “Yes” to all God’s promises (2 Cor. 1:20). Remove Him, and the story becomes a question with no answer, a bridge with no far side.

Thus, both Islam and post-Christian Judaism lack the resolution that only the gospel provides. Islam never had it; Judaism awaits it still.

Evangelistic Implications — Engaging with Fragmented Faiths

What does this mean for Christians engaging with Muslims? It means that one powerful apologetic strategy is to highlight the coherence, beauty, and redemptive power of the Christian story. Rather than beginning with point-by-point doctrinal debates, we might start with the big picture:

- Why are we here?

- What went wrong?

- Can we be rescued?

- What hope is there for the future?

Christianity answers these with a compelling narrative. Islam does not.

This is why former Muslims like Nabeel Qureshi found the gospel not only true but better. It tells the full story—from the Garden to the Cross to the New Jerusalem.

Evangelism, then, can appeal not only to truth but to story. As Alister McGrath reminds us, the gospel is not just correct; it is beautiful, satisfying, and complete.

Conclusion — The Coherence of Christ

In the end, worldviews rise or fall not merely on isolated claims, but on whether they explain the whole. Christianity does. It offers a Creator who is personal, a world that is good, a fall that is tragic, a Savior who is sufficient, and a future that is glorious.

Islam offers moral rules, historical fragments, and divine commands—but no Redeemer, no resurrection, no restoration.

As Greg Bahnsen emphasized, only Christianity provides the preconditions for meaning—moral, rational, historical, and personal. As Francis Schaeffer warned, fragmented systems lead to despair. As John Frame insisted, truth is coherent because it reflects the mind of God.

And as the gospel proclaims, this God is not only true but good—and He invites us into the story He is writing.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

MMXXV

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

If I have listed the content, I think it is worthwhile viewing to educate yourself on the topic, but it may contain coarse language or some opinions I don’t agree with.

Realize that I sometimes use phrases like “trans man”, “trans woman”, “transgender” , “transition” or similar language for ease of communication. Obviously, as a conservative Christian, I don’t believe anyone has ever become the opposite sex. Unfortunately, we are forced to adopt the language of the left to discuss some topics without engaging in lengthy qualifying statements that make conversations awkward.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.