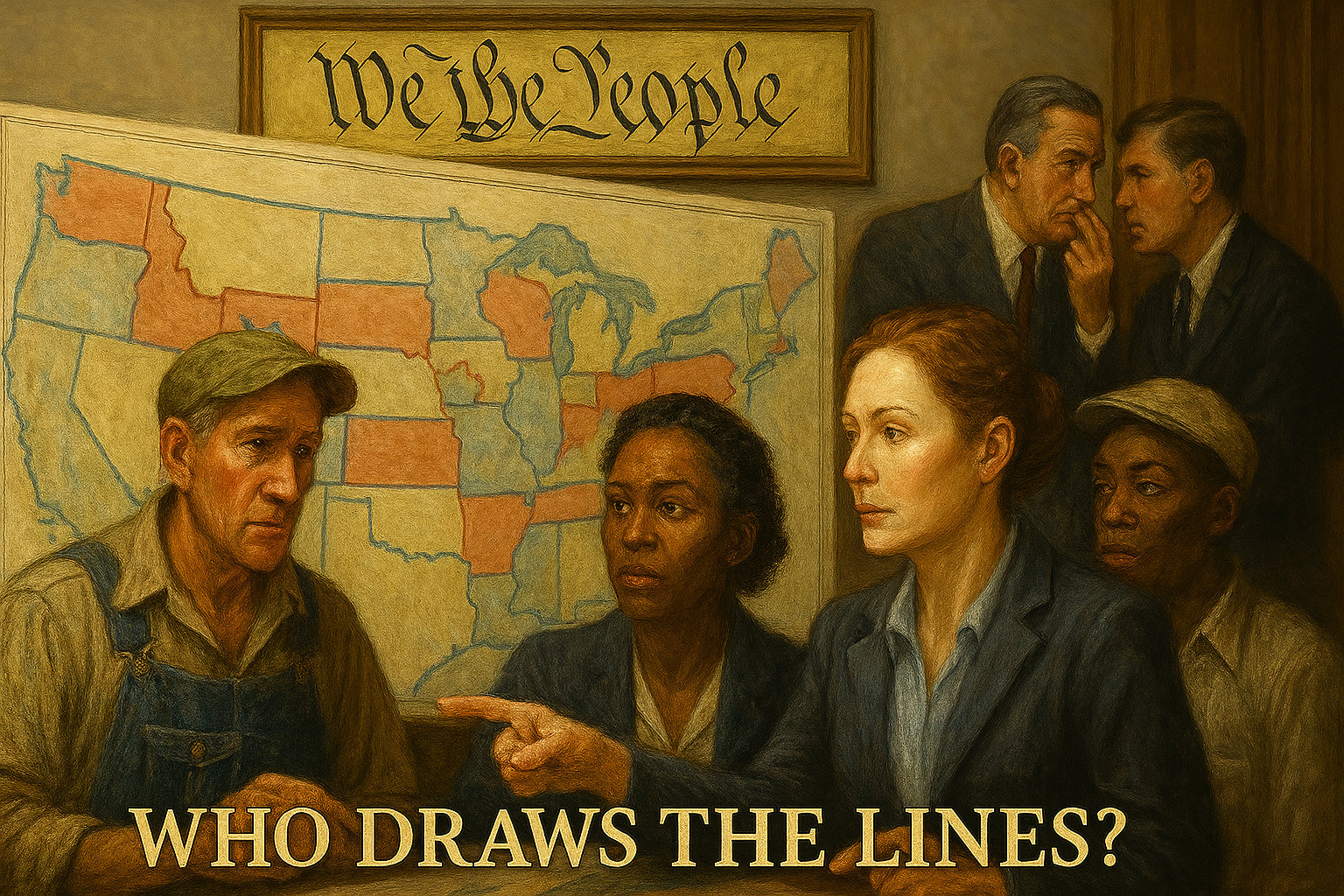

Imagine you’re a referee at a basketball game. But before the game starts, one of the teams gets to draw the boundaries of the court—making their basket closer and the opponent’s farther away. That’s not a fair game. Yet something quite similar happens in American politics, and it’s called gerrymandering.

At its most basic, gerrymandering is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, group, or outcome. In the United States, this mostly applies to congressional and state legislative districts. Every ten years, after the census, districts are redrawn to reflect population shifts. But those in charge of redrawing—often state legislatures—can do so in a way that deliberately benefits their side.

For example, a party in power might draw districts to pack the opposing party’s voters into just a few districts (“packing”) or to spread them thinly across many districts to dilute their influence (“cracking”). The goal is clear: win more seats with fewer votes.

To someone unfamiliar with how American politics works, this might seem odd, even unthinkable. Shouldn’t the people choose their politicians, rather than politicians choosing their people?

Understanding gerrymandering matters—not just for political junkies or lawyers, but for every American citizen. It affects who represents you, what laws are passed, and whether your voice actually counts.

The Current Battle: Gerrymandering in Today’s America

The fight over gerrymandering in the United States today is fierce—and politically loaded. Both Democrats and Republicans accuse each other of rigging maps to entrench power, often taking their complaints all the way to the courts. In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering is a political question beyond the reach of federal courts. In other words, federal judges won’t stop it. That has turned the heat up on state courts, commissions, and legislatures to fight over what is “fair.”

Recent battleground states include:

- North Carolina, where courts have repeatedly tossed out maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders—only for new ones to replace them.

- Ohio, where voters approved reforms to ensure fairer districts, but the state’s redistricting commission has been accused of ignoring them.

- Texas, where claims of racial discrimination in map-drawing have collided with demands for “equity,” resulting in lawsuits and national media attention.

- New York, where Democrats attempted to draw favorable maps only to be rebuked by their own courts.

Each side claims the moral high ground. Democrats often frame the issue around voting rights and racial fairness. Republicans argue for geographic representation and claim that Democratic redistricting commissions are just as partisan, only dressed up in neutral language.

But beneath the rhetoric lies a more troubling truth: the average voter feels powerless. When district lines are drawn with surgical precision to ensure outcomes, it undermines the idea that elections are genuine contests of ideas. And this is not new.

The History of Gerrymandering in the United States

The term “gerrymander” is over two centuries old, and its origin story is a blend of political calculation and cartoon-worthy creativity.

In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry signed a redistricting bill favoring his Democratic-Republican party. One district was so contorted that it resembled a salamander—at least according to a political cartoon in the Boston Gazette. The artist dubbed it the “Gerry-mander.” The name stuck.

Gerry himself might not have invented the practice, but he became its namesake. And the strategy spread quickly.

Early Examples and Party Struggles

Throughout the 19th century, both parties engaged in gerrymandering when given the chance. As states entered the Union, their first congressional maps were often drawn by partisan legislatures eager to stack the deck.

In the Reconstruction era, Southern Democrats drew lines to dilute newly enfranchised black voters. Later, when African Americans migrated to Northern cities, political machines (like Tammany Hall in New York) responded with maps that consolidated power among loyal voters while marginalizing dissent.

By the 20th century, technological advances made gerrymandering even more effective. Detailed census data, precinct-level voting results, and demographic modeling allowed mapmakers to slice and dice populations with unprecedented precision.

Both Democrats and Republicans took advantage. But the impact differed by era.

Mid-20th Century: Democrat Domination

For much of the 20th century, Democrats controlled many state legislatures, especially in the South and Rust Belt. This allowed them to gerrymander aggressively, often creating safe seats that endured for decades. In fact, before the conservative realignment of the 1980s and 1990s, many rural Southern states were dominated by “Blue Dog” Democrats—moderate to conservative by national standards.

The result was a kind of inertia. Incumbents became nearly impossible to defeat, fostering complacency and ideological uniformity. Republicans, lacking control over many state legislatures, found themselves boxed out of power despite winning large shares of the vote nationwide.

Late 20th to Early 21st Century: Republican Resurgence

This imbalance began to change in the 1990s and early 2000s, culminating in a strategic Republican effort after the 2010 census. The GOP launched a coordinated redistricting push called REDMAP (Redistricting Majority Project), which targeted state legislatures in swing states. It worked.

Republicans won control of redistricting in states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, and North Carolina—and drew maps that helped secure a decade of House majorities.

In response, Democrats began pushing for independent redistricting commissions—a reform idea they now champion, though not always apply when they hold power themselves.

This tug-of-war continues today, with each side accusing the other of hypocrisy, while the maps grow more convoluted and voters grow more cynical.

Where the Lines Get Wild: Bizarre Districts and Political Gamesmanship

Some congressional districts in the United States are so oddly shaped they look like a kindergartener’s doodle—except these lines determine real political power. These twisted, spindly, and serpentine boundaries aren’t accidents. They are the result of calculated gerrymandering efforts—designed to carve up voters in a way that benefits one party or weakens another.

Let’s look at some of the worst offenders.

Illinois’s 4th Congressional District – “The Earmuffs”

Possibly the most famous example of absurd redistricting is Illinois’s 4th District, often referred to as “the earmuffs.” Before a recent redrawing, the district consisted of two heavily Hispanic neighborhoods—one on the north side of Chicago, the other on the southwest side—connected by a thin strip running along Interstate 294.

That narrow connector—a literal highway median in places—was less than the width of a football field in some stretches. Yet it was enough to link two demographically similar groups while excluding whiter neighborhoods in between. This maneuver created a safe seat for a Democratic candidate with strong Latino support, but it also made a mockery of geographic coherence.

The shape was so egregious that even liberal reform groups criticized it. And it highlighted a key technique in gerrymandering: pack like-minded voters together to secure a guaranteed win, even if it means drawing borders that defy common sense.

Maryland’s 3rd District – “Blood Spatter”

Maryland, a deep blue state, has also been accused of gerrymandering—by its own liberal judges. The 3rd District has been described as looking like a broken wing or a blood spatter. It weaves and stretches through suburbs of Baltimore in a jagged line designed to capture just enough Democrats while excluding Republican enclaves.

In 2018, a panel of federal judges struck down the map, citing it as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The Supreme Court later declined to intervene in Rucho v. Common Cause, but the criticism remained. Even The Washington Post called the district “a prime example of gerrymandering run amok.”

North Carolina’s 12th District – “The Snake on I-85”

North Carolina’s 12th District has a long history of redrawing and controversy. At one point, it followed Interstate 85 for nearly 100 miles, sometimes only as wide as the freeway itself. The goal was to connect several African American communities to create a majority-black district, but critics said the shape diluted neighboring districts and undermined electoral fairness.

The Supreme Court ruled multiple times that North Carolina’s districts violated constitutional standards—either due to racial gerrymandering or partisan overreach. Even after adjustments, the state continues to face lawsuits over its maps.

Texas’s 35th District – “The Barbell”

Texas’s 35th District, before the latest redrawing, looked like a barbell—linking San Antonio and Austin with a skinny corridor of land that included barely anything in between. Again, the goal was to combine liberal urban areas and create a safe Democratic district. Critics said it ignored regional identity and common community interest, favoring raw political math instead.

Arbitrary or Neutral Redistricting: A Better Way?

As the public grows more aware—and more disgusted—by gerrymandered maps, reformers have proposed more neutral methods for drawing districts. These include:

- Independent Redistricting Commissions

- Computer Algorithms

- Geographic Compactness Standards

- County/City Boundary Integrity Rules

But are these methods truly neutral? Let’s explore the strengths and weaknesses.

Independent Redistricting Commissions: Fair or Faux?

Several states—like California, Arizona, Michigan, and Colorado—have adopted independent or bipartisan commissions to take map-drawing out of politicians’ hands. The idea is simple: if legislators benefit from the maps they draw, they shouldn’t be the ones drawing them.

In theory, these commissions are comprised of equal numbers of Republicans, Democrats, and unaffiliated members. In practice, however, selection processes can be gamed. Some commissions have been accused of leaning left due to the makeup of the applicant pool or biased rules for tie-breaking.

California’s commission, for example, has created more competitive districts—but critics argue that subtle political motives still shape the maps under the surface.

Pros:

- Removes blatant self-interest from the process

- Increases transparency and public input

- Often results in more competitive races

Cons:

- Commissioners may still have ideological biases

- Legal battles still arise over fairness

- “Independence” is sometimes more myth than reality

Algorithmic or Mathematical Redistricting

Some reformers advocate for algorithmic map-making—using computer models to generate districts based on geographic compactness, equal population, and boundary integrity. These models can produce thousands of potential maps and choose the one that minimizes partisan bias.

But this raises questions too. Who writes the algorithm? What values are prioritized? An algorithm can be made to favor competitiveness, or demographic representation, or geographic simplicity—but not all at once. Someone has to choose the values, and that opens the door to political influence.

Pros:

- Transparent and repeatable process

- Reduces emotional or manipulative tactics

- Potential for standardized fairness

Cons:

- Can’t fully capture community or cultural connections

- Algorithms reflect the values programmed into them

- Still needs legal and public oversight

Compactness and Community: Good Ideals, Hard to Define

Courts have sometimes looked for “compactness” as a test of fairness. A compact district avoids tentacles, curves, and appendages. It respects natural geography, city and county boundaries, and keeps communities of interest together.

The problem? “Community of interest” is a vague term. What defines a community—race, income, industry, culture, education? And what happens when those groups are scattered?

Pros:

- Easier for voters to understand

- Prevents the most grotesque map shapes

- Encourages local representation

Cons:

- Hard to define and enforce

- Can unintentionally favor one group or party

- May dilute representation of minority populations

Neutral districting sounds good—and often is better than the status quo. But it’s not a silver bullet. Every method still requires judgment, trade-offs, and honest debate about what values should guide our maps.

In the next section, we’ll take a deeper look at the ideological motivations behind today’s redistricting battles—particularly how the concept of “equity,” as redefined in modern Neo-Marxist ideology, is influencing efforts in places like Texas. We’ll also evaluate whether claims that Democrats have rigged the House of Representatives through gerrymandering hold water.

Equity, Neo-Marxism, and the New Motivation Behind Map Drawing

In recent years, the debate over gerrymandering has acquired a new vocabulary—one that goes beyond simple partisanship or geographic balance. Words like “equity,” “marginalized communities,” “structural oppression,” and “representation justice” now shape the way redistricting is discussed in academic circles, activist groups, and progressive legal organizations.

What’s driving this change? In many cases, it is the influence of Neo-Marxist thought—a worldview that sees power, not principle, as the organizing force of society.

The Shift from “Equality” to “Equity”

Traditionally, American law and civics were guided by the concept of equality—the idea that all citizens should have equal protection under the law and equal voting power. Redistricting under this model aims for equal population in each district and fair processes.

But over the last decade, especially in left-leaning academia and activist movements, the emphasis has shifted to equity. Unlike equality, equity seeks to engineer equal outcomes—by factoring in race, socioeconomic status, and perceived historical disadvantage.

In redistricting, this means districts should not just be equal in size or compact in shape. Instead, they should empower historically underrepresented groups, even if that requires odd boundaries or aggressive racial considerations.

The argument is framed morally: unless marginalized communities are guaranteed to elect representatives who “look like them” or “speak for them,” the system is unjust.

Critics of this equity-based approach, however, argue that it turns the democratic process into a quota system, rooted in identity politics rather than civic representation. They warn that the Neo-Marxist lens views every power imbalance as evidence of systemic oppression, and therefore justifies manipulation of maps to “correct” disparities—regardless of voter preference.

Texas and the Equity Redistricting Debate

Texas offers a prime example of this ideological battle.

After the 2020 census, Texas gained two new congressional seats due to explosive population growth—driven heavily by minority communities, especially Hispanic and Asian populations.

However, when Texas Republicans unveiled their new congressional map in 2021, critics on the Left immediately denounced it as racist and anti-democratic. The key claim? Despite minorities accounting for 95% of Texas’s population growth, the new map did not increase the number of minority-majority districts. In fact, some existing ones were weakened.

Progressive organizations—including the ACLU, MALDEF, and the Brennan Center—argued that this violated the Voting Rights Act and constituted “structural disenfranchisement.”

But Republican mapmakers countered that their maps followed all legal population and contiguity requirements, and that race-neutral redistricting is actually what the law now demands—especially after the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which gutted parts of the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement.

The Neo-Marxist Framework in Practice

To understand how Neo-Marxist ideas influence this debate, we must recognize their core principles:

- Society is divided between oppressors and oppressed.

- Power structures (government, law, economics) reinforce this imbalance.

- Justice means dismantling these structures and redistributing power.

- Outcomes matter more than process or neutrality.

Applied to redistricting, this ideology asserts that even a “fair” process can produce unjust outcomes if marginalized groups don’t win proportional power. Thus, gerrymandering in favor of underrepresented minorities isn’t seen as cheating—it’s seen as corrective justice.

This logic is why some progressive scholars defend Democratic gerrymanders as morally superior to Republican ones. In their eyes, both sides may play the same game, but only one side is doing it to fight systemic oppression.

The problem, of course, is that this redefines democracy itself. It no longer means one person, one vote—it means one ideology reshaping the system to fulfill a utopian narrative. And that, critics argue, is neither democratic nor American.

Have Democrats Rigged the House?

Much of the public discourse on gerrymandering paints Republicans as the sole villains. The New York Times, MSNBC, and major university think tanks often highlight Republican-drawn maps in North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin as proof of “undemocratic” manipulation. And those examples are real.

But the question remains: Have Democrats engaged in similar gerrymandering to secure power in the House of Representatives? The answer is yes—and at times, more effectively than Republicans.

Let’s examine some key facts.

Democrat-Controlled States and Partisan Gerrymandering

- Illinois: The Democrat-dominated legislature drew one of the most aggressive maps in the country after 2020, eliminating Republican-held seats and creating oddly shaped districts that meander through Chicago suburbs. The goal was clear: squeeze out the GOP in a state that already leans blue.

- Maryland: Democrats attempted to redraw maps to flip a Republican-held district, despite already holding 7 of 8 congressional seats. A state judge eventually blocked the map for extreme partisanship, calling it a “product of extreme gerrymandering.”

- New York: The Democrat-led legislature ignored its own independent commission and drew a map that would have handed Democrats an overwhelming edge—22 seats to the GOP’s 4. But the state’s highest court struck it down, citing unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering.

In each case, Democrats tried to rig the maps in their favor—and often went further than Republicans. The difference? Their actions were occasionally rebuked by Democrat-appointed judges, suggesting internal pushback that the GOP often doesn’t face in red states.

The 2022 House Map: A Net Republican Gain, But Narrow

Despite all the noise about Republican gerrymandering, Democrats gained ground through aggressive map-drawing after 2020. According to an analysis by the Cook Political Report, Democratic-drawn maps actually netted them more safe seats than GOP maps did.

This is partly because blue states with declining populations (like New York and Illinois) tried to preserve their influence, while red states with growing populations (like Texas and Florida) had to dilute their gains across new districts.

In other words, Republicans played defense in growing states, while Democrats played offense in declining states.

By 2022, even liberal outlets like NPR admitted that the national congressional map was roughly balanced in terms of partisan bias, with only a slight tilt toward Republicans—far less than in 2012 or 2014.

This undermines the narrative that Republicans have “rigged” the House entirely through gerrymandering. In reality, both parties exploit redistricting when they can, and both face limits—either judicial, demographic, or geographic.

What Was the Original Purpose of Congressional Districts?

To evaluate whether modern gerrymandering honors or violates the Founders’ vision, we need to go back to the original design of the U.S. House of Representatives.

According to Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, the House was intended to reflect the will of the people, with representation based on population. The number of seats would grow with the population (until capped at 435 in 1929), and each member would represent a district of roughly equal population size.

However, the Framers also understood the geographic diversity of the United States—its sprawling rural areas, coastal cities, and regional identities. This is why they gave each state at least one representative, regardless of population, and allowed state legislatures to control district drawing. The system aimed to balance the power of individuals and communities, both urban and rural.

In the early years of the republic, congressional districts were often large, geographically coherent, and tied to county or regional lines. They represented real communities with shared economic and cultural interests—agrarian, mercantile, coastal, inland.

So while the House was designed to reflect population, there was also a practical respect for geographic identity and community structure—something modern gerrymandering has largely abandoned.

Urban vs. Rural Power

In many redistricting debates today, rural voters feel outnumbered and outmaneuvered by densely packed urban centers. Cities grow rapidly, concentrate political activism, and dominate media narratives. Meanwhile, rural areas—though spread out—still reflect a large percentage of the population across many states.

Critics argue that the current system often dilutes rural influence, especially when urban areas are used to “crack” rural regions into smaller voting blocs. This fuels resentment and contributes to the perception that the government no longer represents the whole country—only its city cores.

While the original constitutional intent wasn’t to give “more power” to rural voters per se, it did value local community identity, and assumed that districts would represent coherent, contiguous populations. The fracturing and manipulation we now see with modern gerrymandering—in both urban and rural areas—betrays that vision.

Can Gerrymandering Be Reformed?

If the current situation offends both common sense and constitutional spirit, what can be done about it?

Many Americans support reform. Polls consistently show that over 70% of voters oppose partisan gerrymandering. But solutions vary widely, and each comes with trade-offs.

Strengthening State Constitutions

Some states have amended their constitutions to ban or restrict partisan gerrymandering, using language that prioritizes compactness, competitiveness, or respect for natural boundaries. Courts in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Ohio have used these laws to strike down partisan maps—though results have been mixed.

This route respects federalism and allows states to serve as laboratories of democracy. But it also means uneven standards across the country.

Independent or Bipartisan Redistricting Commissions

As discussed earlier, these commissions aim to remove political self-interest. While imperfect, they often produce less extreme maps than legislatures. However, for these commissions to work, they must be designed transparently, with clear selection rules and genuine political balance.

States like Arizona and Michigan offer hopeful models, while others—like New Jersey—have seen their commissions devolve into partisan gridlock.

Federal Legislation (Unlikely in Current Climate)

Some lawmakers have proposed federal standards for redistricting, such as the For the People Act, which would mandate independent commissions nationwide. However, constitutional questions about federal overreach, combined with deep partisan mistrust, make such proposals unlikely to succeed.

And ironically, even well-meaning reforms risk being weaponized by partisan actors. In today’s ideological climate, “neutrality” itself is suspect, depending on who defines it.

Final Reflections: What Gerrymandering Says About Us

Gerrymandering is not just a legal or political problem. It’s a moral and cultural problem. At its root, it reflects a loss of confidence in fair play—a willingness to bend the rules to gain or maintain power. That’s a warning sign, not just for democracy, but for national unity.

Both major parties have participated. Both have accused the other. And both have, at times, rightly earned the public’s cynicism.

But when everything becomes a game of strategy—when even our voting maps are treated like battlefields instead of forums for civic representation—we lose something deeper: trust.

We lose the belief that we can reason together as a people. We begin to see every election not as a contest of ideas, but as a pre-rigged spectacle—a theater of winners and losers where the lines were drawn before the votes were cast.

That’s not what the Founders intended. It’s not what Americans deserve.

The solution isn’t simple. It won’t be found in a magic algorithm or a new commission. The only long-term remedy is a renewed public virtue—a shared conviction that power is not the highest good and that fairness, even when it costs us politically, is worth pursuing.

Reforming gerrymandering won’t fix all our national divisions. But it’s a meaningful place to start—because representation is not just about districts and maps. It’s about dignity, community, and trusting the people.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

MMXXV

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

If I have listed the content, I think it is worthwhile viewing to educate yourself on the topic, but it may contain coarse language or some opinions I don’t agree with.

I use words that reflect the “woke” culture and their re-definitions sometimes. It is hard to communicate effectively without using their twisted vocabulary. Rest assured that I do not believe gender ideology or “Progressivism”. Words and phrases like “trans man”, “trans women” , “transgender”, “transition” or similar words and phrases are nonsensical and reflect a distorted, imaginary worldview where men can become women and vice-versa. The word “Progressive” itself is a propagandistic word that implies the Progressives are the positive force in society, whereas in reality their cultic belief system is very corrosive to mankind.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.