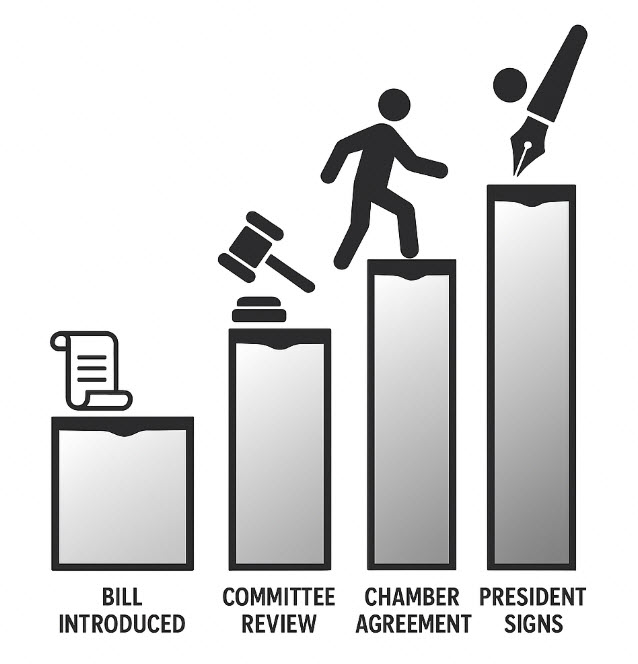

The process of passing a federal law in the United States is often described as a journey—from the birth of an idea to the moment the President signs it into law. But this journey is far from simple. Unlike the Schoolhouse Rock version that simplifies it to a catchy tune, the real path is filled with political landmines, procedural roadblocks, and powerful gatekeepers who can quietly or publicly kill a bill before it sees the light of day. In this article, we’ll explore the federal legislative process, from introduction to enactment, identify key decision-makers who can stop a bill at each phase, define important terms, and analyze the political reasoning behind common procedural barriers.

Definitions

To help readers who may not recall the finer points of high school civics, here are key terms used in the legislative process:

- Bill: A proposal for a new law or an amendment to an existing one.

- Sponsor: The Member of Congress who introduces the bill.

- Committee: A group of legislators assigned to review bills on specific subjects (e.g., agriculture, judiciary).

- Subcommittee: A smaller unit within a committee focusing on more specialized topics.

- Filibuster: A prolonged speech in the Senate intended to delay or block a vote.

- Cloture: A Senate vote (requiring 60 votes) to end a filibuster.

- Hold: An informal Senate practice where one Senator can delay proceedings on a bill.

- Reading: A formal stage in the legislative process—bills typically receive three “readings.”

- Pocket Veto: When the President does not sign a bill within 10 days and Congress adjourns during that period, effectively killing the bill.

Step 1: Drafting and Introduction

What Happens:

A bill begins as an idea, which may originate from a Member of Congress, a constituent, a think tank, or a lobbyist. Only a Senator or Representative can formally introduce it.

Kill Points:

- A Member of Congress may choose not to introduce a bill due to political pressure, lack of support, or fear of controversy.

- A party leader or influential committee member might discourage introduction if it conflicts with the party’s agenda.

Step 2: First Reading and Committee Referral

What Happens:

Upon introduction, the bill is “read” for the first time—a procedural step where it is assigned a number and referred to the appropriate committee.

Kill Points:

- Committee Chairs hold great power. They can refuse to schedule hearings, effectively killing the bill.

- Leadership in both chambers can influence whether a bill receives committee attention.

Political Reasons:

- Chairs may kill bills that oppose the majority party’s platform or that might split the caucus.

- Leadership may prioritize limited floor time for bills with broader consensus.

Step 3: Committee and Subcommittee Action

What Happens:

The committee may refer the bill to a subcommittee for further examination, expert testimony, and possible amendment. After review, it may be approved and returned to the full committee.

Kill Points:

- Subcommittees can decline to act or recommend that the bill not move forward.

- Full committees can vote down the bill or fail to take action, letting it “die in committee.”

Political Reasons:

- Controversial bills may be avoided to protect members from tough votes.

- Lobbyist or donor influence may persuade members to block legislation quietly.

Step 4: Second Reading and Floor Scheduling

What Happens:

If approved by the committee, the bill is read a second time and scheduled for debate and amendment on the chamber floor.

Kill Points:

- House Rules Committee decides if and how a bill is debated. It can block or restrict debate.

- In the Senate, the Majority Leader may refuse to schedule the bill.

- A Senator can place a hold or threaten a filibuster to delay action.

Political Reasons:

- Floor time is limited; leaders may prioritize only winnable or unifying legislation.

- Senators may oppose bills for ideological reasons or to obstruct the opposing party’s success.

Step 5: Floor Debate, Amendments, and Voting

What Happens:

The bill is debated, often amended, and then subjected to a vote. A simple majority is needed to pass.

Kill Points:

- Poison-pill amendments may be added to make the bill politically unpalatable.

- Senators may filibuster the bill unless 60 votes are secured to invoke cloture.

- Failure to secure a majority vote ends the bill’s journey in that chamber.

Political Reasons:

- Senators may use the filibuster to gain concessions or delay other legislation.

- Opponents may amend a bill to force the sponsoring party into politically damaging positions.

Step 6: The Other Chamber

What Happens:

The process repeats in the other chamber (House or Senate). It may approve the bill as-is or pass a different version.

Kill Points:

- The second chamber’s committees or leaders may refuse to take up the bill.

- Political disagreements between chambers may stall progress indefinitely.

Political Reasons:

- Differences in party control can make cooperation difficult.

- Strategic stalling may be used to run out the legislative clock.

Step 7: Conference Committee

What Happens:

If both chambers pass different versions, a conference committee of Senators and Representatives works out the differences.

Kill Points:

- Failure to reach a compromise results in the bill dying in conference.

- One chamber may refuse to vote on the conference version.

Political Reasons:

- Parties may not want to be seen as compromising on core values.

- Hidden provisions (earmarks) can spark public backlash.

Step 8: Final Passage and Enrollment

What Happens:

Both chambers must pass the exact same version of the bill. If passed, it is “enrolled” and sent to the President.

Kill Points:

- Either chamber may reject the conference version, ending the bill.

Step 9: Presidential Action

What Happens:

The President may:

- Sign the bill – it becomes law.

- Veto the bill – it returns to Congress.

- Do nothing:

- If Congress is in session after 10 days, the bill becomes law.

- If Congress adjourns, it results in a pocket veto.

Kill Points:

- Presidential veto sends the bill back to Congress.

- Pocket veto kills it silently if Congress adjourns.

Political Reasons:

- The President may veto to signal strength or please a political base.

- Pocket vetoes are used to avoid direct confrontation.

Step 10: Veto Override (Rare)

What Happens:

Congress can override a veto with a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

Kill Points:

- If either chamber falls short, the veto stands, and the bill dies.

Political Reasons:

- Overrides are rare due to the difficulty of assembling a two-thirds majority.

- Members may support the bill but avoid an override vote to remain loyal to their party’s President.

Conclusion

The U.S. legislative process is intentionally slow and difficult. Every stage contains multiple off-ramps where a bill can be halted by individuals or small groups. While frustrating to some, this system was designed by the Founders to ensure that laws reflect broad consensus and are not the result of temporary passions or narrow interests. Behind every bill that becomes law is a story of perseverance, negotiation, and often, intense political struggle. Just as importantly, behind every bill that dies is a story of resistance—sometimes principled, sometimes partisan, but always rooted in the complexities of our constitutional republic.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

Some sources of information may reflect a libertarian and/or atheistic perspective. I may not agree with all of their opinions, but they offer some worthwhile comments on the topic under discussion.

Additionally, language used in the videos may be coarse. Coarse language does not reflect my personal standards.

Finally, those on the left often criticize my sources of information, which are primarily conservative and/or Christian. Truth is truth, regardless of how we feel about it. Leftists are largely led by their emotion rather than facts. It is no small wonder that they would criticize the sources that I provide. And, ultimately, my wordview is governed by Scripture. Many of my critics are not biblical Christians.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something, though.

I will continue to add items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.