Most Americans have heard the phrase “the parties switched.” Yet few can explain what that means, when it happened, or how it unfolded. The truth is more complex than the slogans of modern politics. The Democratic and Republican parties did not swap identities overnight; they evolved over nearly two centuries through a combination of moral conflict, economic upheaval, immigration, and shifting definitions of freedom and progress.

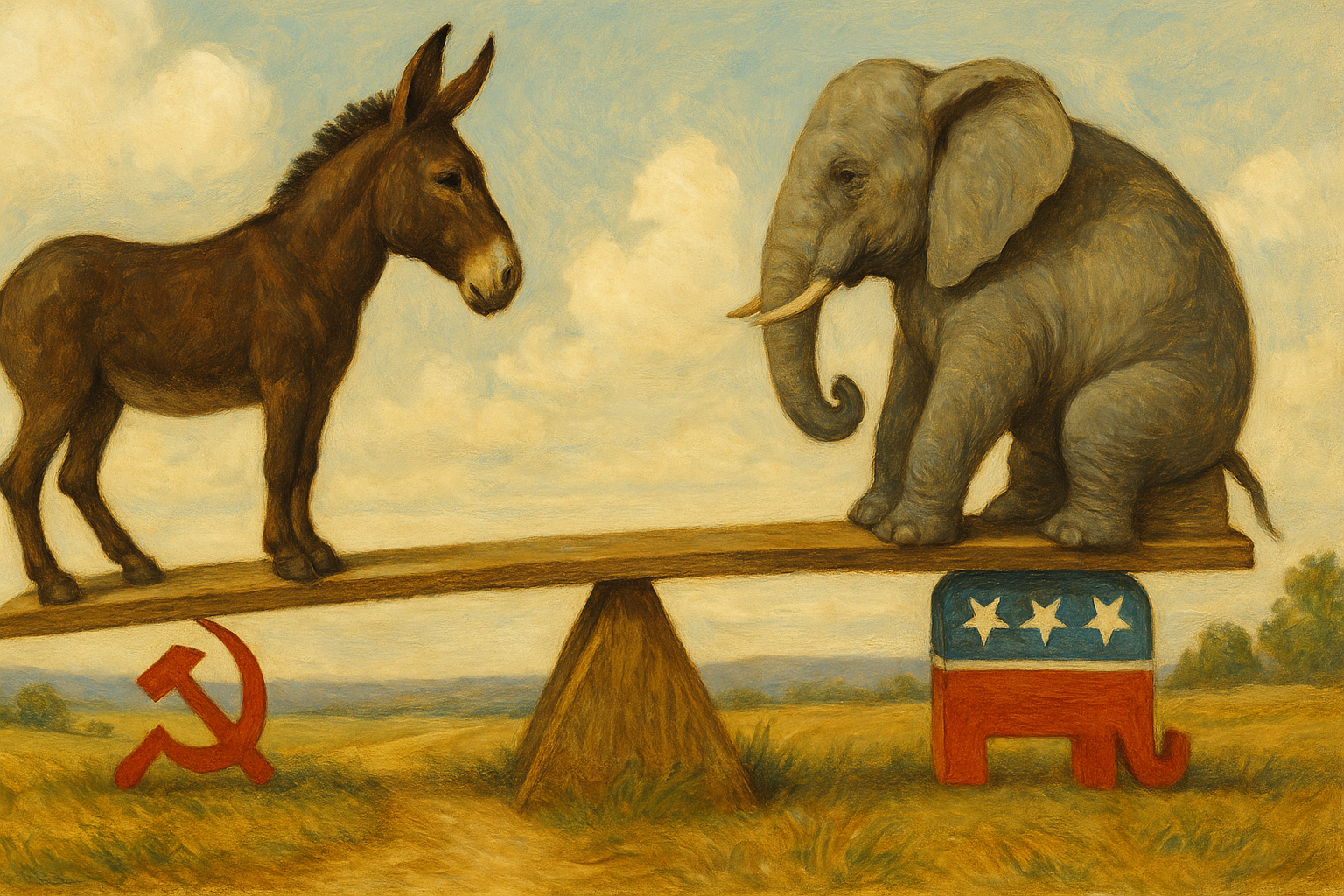

This story is not one of betrayal but of transformation. Each party began with ideals that made sense in its time, and both continually re-shaped themselves to fit the moral and social crises of the nation. The ideological DNA of both parties—Democrats and Republicans alike—has mutated under the pressures of Progressivism, industrialization, civil rights, and, in our own era, Neo-Marxist and postmodern social activism.

To understand American politics today, we have to walk through the eras that formed—and re-formed—those identities.

The Jacksonian World (1820s–1850s): The Birth of the Democratic Party

The Democratic Party emerged from the populist surge that followed the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s movement was fiercely democratic in style but deeply contradictory in substance.

Ideology of Early Democrats

Jacksonian Democrats distrusted elites—bankers, aristocrats, and centralized power. They championed the “common man,” which in practice meant the white common man. Their goals included:

- Ending monopolies and centralized banking (Jackson’s “Bank War”);

- Expanding land ownership and westward settlement;

- Protecting slavery where it existed;

- Restricting federal involvement in economic or moral life.

They preached liberty but practiced exclusion. They saw democracy as local control, not federal oversight.

Northern vs. Southern Democrats

Both wings shared this populist style but differed in their material base:

- Southern Democrats defended slavery and agrarian hierarchy. “Freedom” meant freedom from federal interference.

- Northern Democrats appealed to immigrant laborers and small farmers. Many accepted slavery’s existence but opposed its expansion.

Economic and Moral Tensions Deepen

Additional fractures widened between the two wings over economics and radical activism.

Tariffs were a long-standing grievance: Northern Democrats—whose states benefited from industry—often supported protective tariffs to shield manufacturing. Southern Democrats, dependent on exporting cotton and importing goods, saw tariffs as a tax on their livelihood. To the Southern mind, the tariff issue symbolized Northern exploitation and growing federal intrusion into local economies.

Simultaneously, extreme abolitionists in the North—such as John Brown and the followers of William Lloyd Garrison—pushed beyond the mainstream Democratic position. Their advocacy of violent or immediate emancipation alienated even moderate Northerners and confirmed Southern fears that abolition was not merely a moral crusade but a direct threat to Southern life and security.

These economic and ideological rifts made the Democratic coalition increasingly untenable. While moderates sought compromise, radicals on both sides hardened into rival moral visions of America—one viewing slavery as sin, the other as a social necessity ordained by local sovereignty.

The fragile alliance cracked when the question arose: should new western territories allow slavery? Northern Democrats like Stephen Douglas proposed popular sovereignty (let settlers decide). Southern Democrats demanded federal guarantees for slavery everywhere. By 1860 the party split, ensuring Abraham Lincoln’s Republican victory.

The Birth of the Republican Party (1850s–1860s): Liberty as a Moral Crusade

The Republican Party formed in the 1850s as a coalition of Northern Whigs, Free-Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats. Its founders believed that free labor—not slave labor—was the foundation of national prosperity and moral order.

Core Republican Ideas

- Opposition to slavery’s expansion (though not initially to its immediate abolition);

- Support for protective tariffs to build industry;

- Federal investment in railroads, education, and homesteads;

- A moral sense of national destiny rooted in Protestant reform.

Republicans were the party of moral activism—a mixture of evangelical Christianity, market capitalism, and belief in national improvement. They were Progressives before the Progressive Era, using government power to achieve moral ends.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Lincoln’s war aims evolved from preserving the Union to ending slavery. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments enshrined abolition, citizenship, and black voting rights. The Republican Party became the champion of equal protection under law.

But after Lincoln’s death and the exhaustion of Reconstruction, Northern moral idealism waned. The South “redeemed” itself with Jim Crow segregation, and the Republican Party turned toward business and industry.

The Gilded Age (1870s–1890s): The Business Republicans and the Redeemer Democrats

After the Civil War, both parties reorganized around class and regional interests rather than moral crusades.

Republicans

- Dominated the North and West.

- Favored tariffs, gold standard, industrial growth, and a limited social safety net.

- Became the party of corporate America—railroads, steel, finance.

- Claimed to uphold “Union” and “progress,” but drifted away from racial equality.

Democrats

- Controlled the “Solid South” through disenfranchisement and segregation.

- Opposed Reconstruction and civil rights enforcement.

- In the North, relied on urban immigrant machines (Tammany Hall in New York, the Pendergast machine in Kansas City).

- Opposed prohibition and moral reform movements led by Protestant Republicans.

At this point, Southern Democrats were culturally conservative and racially reactionary, while Northern Democrats were urban populists, defending ethnic working classes from moralistic reformers.

The alliance endured because both wings despised Republican elites—Southern planters hated their meddling, and Northern immigrants resented their moralizing.

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s): Science, Reform, and the Moral Revival of Politics

Progressivism erupted as a response to industrial abuses—child labor, monopolies, corruption, poverty. It was less a single ideology than a temperament: faith in expertise, government regulation, and social reform.

Republican Progressives

- Theodore Roosevelt, Robert La Follette, and others sought to regulate big business and improve labor conditions.

- They believed government could be a force for moral good.

- Their Protestant moral zeal echoed the reform spirit of the old abolitionists.

Democratic Progressives

- In the South, they pursued “modernization” under white supremacy.

- In the North, they pushed for labor reforms and municipal clean-up but resisted cultural puritanism (especially prohibition).

The Immigrant Influence

- Millions of new immigrants—Irish, Italians, Poles, Jews—poured into cities.

- Many brought socialist or Catholic communitarian ideals, reshaping the Democratic base.

- Republicans viewed them suspiciously; Democrats courted them as new voters.

Tension between the Wings

- Southern Democrats used Progressive rhetoric to justify racial control.

- Northern Democrats used it to demand labor rights and social welfare.

- Republicans split between reformers (Roosevelt) and corporate conservatives (Taft, Coolidge).

By the 1920s, Progressivism had infected both parties but produced different fevers. Republicans used it for efficiency and conservation; Democrats used it for economic populism. Yet neither party addressed race honestly. That reckoning would come later.

But beneath this swirl of reform and industrial optimism, a quieter revolution was underway in America’s pulpits—one that would reshape not only churches but the moral vocabulary of both parties.

Interlude: The Loss of Theological Confidence and the Moral Reordering of American Politics

Theological Upheaval and Political Morality

Beneath the surface of Progressivism, a subtler revolution was unfolding inside American churches. The rise of “higher criticism” and liberal theology in the late 19th century redefined the meaning of truth and sin. Scripture came to be treated as ancient literature rather than divine revelation, and salvation as social reform rather than reconciliation with God. This “modernist” faith, sometimes called the Social Gospel, fused easily with the optimism of the Progressive Era and infused politics with moral fervor divorced from orthodoxy.

Leaders like Walter Rauschenbusch and Harry Emerson Fosdick reimagined Christianity as humanitarian activism. The movement’s moral vocabulary—oppression, liberation, and social justice—soon migrated into the Democratic Party’s evolving platform, especially in its northern and urban branches. The church’s pulpit became a public forum, and “redemption” meant the improvement of social conditions rather than repentance before God.

Orthodox Christians like R.A. Torrey and J. Gresham Machen saw this as a theological betrayal. They warned that Christianity was being reduced to sociology and that political idealism was replacing the gospel. Their “Fundamentalist” defense of biblical authority would not only split denominations—it would eventually divide the political conscience of the nation.

As liberal Protestantism moved leftward, conservative believers—finding no home in this new moral order—gradually gravitated toward the Republican Party, which still defended individual accountability, traditional morality, and skepticism of social engineering. By the mid-20th century, what had begun as a theological crisis had become a political one. The American two-party system would never again share a common moral vocabulary.

What began as a quarrel over Scripture would soon become a battle over the soul of the nation—one fought not only in seminaries but in the ballot box

The New Deal Realignment (1930s–1940s): The Rise of the Modern Democratic Coalition

The Great Depression shattered laissez-faire orthodoxy. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal redefined government’s role.

The New Democratic Coalition

- Northern urban immigrants and labor unions;

- Southern whites;

- Black voters (gradually switching from the party of Lincoln);

- Intellectuals and reformers.

FDR fused Progressive faith in planning with Democratic populism. His programs—Social Security, labor protections, public works—gave ordinary people a sense that Washington cared.

Southern Democrats’ Role

- Supported New Deal spending that flowed to their districts;

- Ensured programs didn’t threaten segregation;

- Traded votes for local control of racial policy.

Republicans’ Position

- Reduced to a minority, they portrayed themselves as defenders of fiscal responsibility and individual enterprise.

- Some progressive Republicans (like Wendell Willkie) accepted aspects of the welfare state but opposed its scale.

The New Deal thus cemented the Democratic Party as the party of economic intervention—and laid the foundation for later conflicts over civil rights and federal power.

The Post-War Era (1945–1960): Cold War Liberalism and Cracks in the Coalition

After World War II, America faced new questions: prosperity, communism, and racial equality.

Democratic Tensions

- Northern liberals pushed civil rights and expanded welfare.

- Southern Democrats (“Dixiecrats”) revolted against desegregation.

- The 1948 election saw Strom Thurmond run as a States’ Rights Democrat.

- President Truman integrated the military and advanced civil rights, alienating the South.

Republican Rebirth

- Under Dwight Eisenhower, Republicans moderated. They accepted parts of the New Deal (interstate highways, Social Security) while emphasizing anti-communism, patriotism, and cautious governance.

- The GOP became the party of suburban respectability—pro-business, anti-socialism, but not yet radical.

Meanwhile, intellectuals like William F. Buckley Jr. forged a new conservative movement: anti-communist, pro-free market, and morally traditional. It would soon merge with Southern discontent to reshape the GOP.

The Civil Rights Revolution (1950s–1970s): When the Parties Truly Diverged

Civil rights was the moral test that broke the 19th-century Democratic alliance.

Northern Democrats

- Embraced federal civil rights enforcement under Kennedy and Johnson.

- Passed the Civil Rights Act (1964) and Voting Rights Act (1965).

- Attracted black voters and liberal intellectuals.

Southern Democrats

- Viewed these laws as federal overreach.

- Many defected to the Republican Party over the next two decades.

Republican Realignment

- Barry Goldwater opposed the Civil Rights Act on libertarian grounds.

- Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” appealed to conservative whites via states’ rights, law-and-order, and patriotism.

- Evangelical Christians, long apolitical, began aligning with Republicans over cultural issues like abortion and school prayer.

By the 1970s, the moral inversion was complete:

- Democrats had become the party of federal activism, equality, and social reform.

- Republicans became the party of localism, traditional morality, and free enterprise.

By the end of the 1960s, the old liberal Protestant conscience that had once animated both parties had fragmented. Its moral passion for justice survived, but the theological foundation that once anchored it in Scripture did not. As faith receded, politics inherited its moral absolutism.

The Cultural Revolution and the New Left (1960s–1980s)

The civil rights movement birthed a larger cultural revolution. Feminism, environmentalism, sexual liberation, and anti-war activism redefined “Progressive” politics.

Democratic Transformation

- The party moved from working-class populism toward identity-based activism.

- The old blue-collar, church-going Democrats—ethnic Catholics, small-town laborers—felt displaced.

- The 1972 McGovern campaign symbolized the new liberalism: peace, multiculturalism, environmentalism, and expanded personal rights.

Republican Response

- The GOP under Reagan (1980) fused economic conservatism, moral traditionalism, and patriotism.

- Southern whites and Northern ethnic Catholics migrated to the Republican camp.

- “Reagan Democrats” symbolized this crossover: socially conservative, economically moderate, and tired of moral chaos.

The parties had fully swapped their cultural centers:

- Democrats became secular and cosmopolitan.

- Republicans became religious and populist.

Immigration and the Global Progressive Consensus (1980s–2000s)

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 had already diversified the nation. By the late 20th century, immigration from Latin America and Asia reshaped urban politics.

Democratic Effects

- New immigrants largely favored Democrats, who emphasized inclusion, welfare access, and multiculturalism.

- Progressive intellectuals reframed politics around “systemic inequality” rather than individual liberty.

- Universities, media, and NGOs spread this ethos nationally.

Republican Effects

- Split between pro-business advocates of open borders and populists demanding enforcement.

- Cultural conservatives warned that mass immigration diluted national cohesion.

- The GOP became increasingly divided between corporate globalists and cultural nationalists.

Meanwhile, Democrats deepened their alliance with academia and media, which increasingly adopted a postmodern interpretation of justice—truth as narrative, morality as identity, politics as moral theater.

The Neo-Marxist and Postmodern Turn (1990s–Present)

Modern “Progressivism” is no longer merely reformist; it has absorbed ideas from Neo-Marxism (critical theory, intersectionality) and postmodernism (skepticism of objective truth).

Core Assumptions of the New Progressivism

- Society is structured by systems of oppression (race, gender, sexuality, class).

- Language and culture create power, not just laws or economics.

- Liberation requires deconstructing traditional norms—family, gender roles, religion, national identity.

How It Reshaped the Democratic Party

- The moral energy that once targeted slavery and monopolies now targets cultural “hegemony.”

- The party’s base shifted to educated elites, urban activists, and identity-based movements.

- Traditional Democrats—rural, religious, patriotic—found themselves politically homeless.

Republican Counter-Movement

- The modern GOP, beginning with Reagan and culminating in the populist surge under Donald Trump, redefined itself as the defender of tradition, national identity, and middle-class stability.

- The cultural lines hardened: Democrats became the moral reformers of a secular creed; Republicans the defenders of inherited norms.

Ironically, the roles had reversed since the 19th century:

- The Democratic Party now uses federal and corporate power to advance moral crusades.

- The Republican Party now waves the banner of localism and resistance to centralized authority—the old Jacksonian posture.

The Present Landscape: Two Moral Religions

Today’s political divide is not simply economic but theological in nature.

Each party embodies a different moral vision of reality.

| Party | Historical Roots | Modern Creed |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | Jacksonian populism → Progressive reform → New Left activism | Moral equality through government, identity-based justice, globalism, and technocratic management. |

| Republican Party | Abolitionist moralism → Business conservatism → Religious and populist revival | Ordered liberty through tradition, free enterprise, and limited government rooted in natural law and faith. |

The modern Progressive Left defines virtue as inclusion and equality; modern Conservatives define virtue as order and fidelity to inherited truth. Both claim moral righteousness, but their sources of authority differ—one trusts the state and the social engineer, the other the Creator and the moral law.

Conclusion: The Long Arc of Party Evolution

Over two centuries, both parties have traded moral vocabularies.

- The Democrats began as defenders of individual liberty and local control, then evolved into promoters of centralized moral reform.

- The Republicans began as reformers and moral crusaders, then evolved into defenders of tradition and restraint.

The engine driving these reversals has always been Progressivism—the recurring American belief that government and moral enlightenment can perfect society. Whether in the hands of 19th-century evangelicals, 20th-century technocrats, or 21st-century social activists, Progressivism has served as both a conscience and a temptation: the impulse to save the world by decree.

Today’s ideological conflict is therefore the latest phase of an old struggle:

liberty versus moral control, local authority versus central expertise, inherited order versus perpetual revolution.

The parties have changed colors, slogans, and rhetoric, but the battle between these principles endures. It always will—because it mirrors a deeper division within human nature itself: the longing for freedom and the longing for redemption through power.

S.D.G.,

Robert Sparkman

MMXXV

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

If I have listed the content, I think it is worthwhile viewing to educate yourself on the topic, but it may contain coarse language or some opinions I don’t agree with.

I use words that reflect the “woke” culture and their re-definitions sometimes. It is hard to communicate effectively without using their twisted vocabulary. Rest assured that I do not believe gender ideology or “Progressivism”. Words and phrases like “trans man”, “trans women” , “transgender”, “transition” or similar words and phrases are nonsensical and reflect a distorted, imaginary worldview where men can become women and vice-versa. The word “Progressive” itself is a propagandistic word that implies the Progressives are the positive force in society, whereas in reality their cultic belief system is very corrosive to mankind.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something afterwards, though.

I will continue to add videos and other items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.