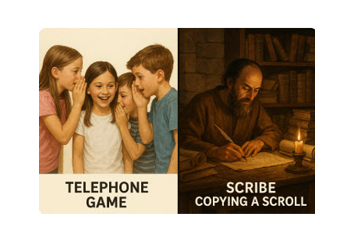

For generations, skeptics of Christianity have spread a popular analogy to undermine confidence in the reliability of the Bible: the so-called “telephone game.” In this game, a message is whispered from person to person down a line, and by the time it reaches the final person, the sentence is comically distorted. Critics claim this is analogous to how the Bible was transmitted over centuries: copied, recopied, mistranslated, manipulated, and mutated—until we no longer know what the original writers said. It is a compelling image—emotive and easily visualized—but it is deeply flawed.

As scholars like Daniel Wallace, Michael Kruger, and Wes Huff have thoroughly demonstrated, the transmission of the Bible was not like a children’s whispering game. Rather, it more closely resembles the careful copying of legal documents or scribal practice in ancient libraries, with checks and balances, extensive manuscript attestation, and a broad textual tradition spanning centuries and continents. In this essay, we will walk through the actual transmission process of the Bible—from the autographs (original writings) to a modern English version like the English Standard Version (ESV)—and examine why this journey inspires confidence, not doubt.

The Autographs: Inspired and Inerrant

The process begins with the autographs, or the original manuscripts written by the biblical authors themselves—Moses, David, Isaiah, Paul, John, and others. Christians who affirm biblical inerrancy, as outlined in the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (1978), believe these autographs were breathed out by God (2 Tim. 3:16), without error in all that they affirm.

These autographs were written in Hebrew (for most of the Old Testament), Aramaic (a few portions), and Koine Greek (for the entire New Testament). The originals were quickly disseminated, read aloud in churches (Col. 4:16; 1 Thess. 5:27), and copied. From the very beginning, the documents were seen as authoritative—bearing apostolic or prophetic authority—and were thus treated with great reverence.

However, no original autographs are known to exist today, which leads many to ask: Can we trust the Bible if we don’t have the originals? The answer, as we’ll see, is a resounding yes.

Copying the Text: Scribes and Manuscript Tradition

The telephone game analogy fails at this point. In that game, the message is passed along orally, one person at a time, with no way to check the original. The biblical transmission process was entirely different.

As Dr. Wes Huff explains, “New Testament textual transmission didn’t happen in a single line of succession but rather in multiple streams, with many people making many copies, creating a wealth of manuscript data.” This is known as multi-stream copying, not linear copying.

The Old Testament:

The Masoretes (roughly 6th–10th century A.D.) are often credited with preserving the Hebrew Bible with stunning accuracy. These scribes used counting systems to ensure exactness: tallying the number of letters, words, and lines in a text, and noting the middle word and letter of each book. Any mistake led to the entire manuscript being discarded.

Recent discoveries, especially the Dead Sea Scrolls, have validated this precision. For example, Isaiah manuscripts from Qumran (2nd century B.C.) show over 95% word-for-word consistency with the Masoretic Text a thousand years later.

The New Testament:

The New Testament is the best-attested ancient document in existence. We have over 5,800 Greek manuscripts, with more than 20,000 total manuscripts in various languages (Latin, Syriac, Coptic, etc.). Some fragments date to within decades of the original writings (e.g., the John Rylands Fragment, P52, dated c. 125 A.D.).

Dr. Daniel Wallace, founder of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM), notes: “No classical literature enjoys nearly the wealth of manuscript evidence that the New Testament does.”

This wealth allows scholars to compare manuscripts across regions and centuries to reconstruct the original text with a high degree of confidence.

Textual Criticism: Recovering the Original Wording

The next major phase is textual criticism, a discipline that aims to determine the original wording of a text based on the surviving copies. Critics wrongly assume we don’t know what the Bible originally said. In truth, we are extraordinarily close—likely within 99.9% accuracy.

When small differences do occur between manuscripts, the vast majority are minor: changes in spelling, word order, or duplications caused by scribal error. Virtually none affect essential Christian doctrine.

Michael Kruger observes, “The textual variants that do exist are known, cataloged, and scrutinized. The idea that textual corruption has obscured the gospel message is not only false but ignores the data that we have.”

One of the most trusted editions for English Bible translators is the Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament, now in its 28th edition. This critical text is based on careful analysis of the best available manuscripts using well-established principles of textual criticism.

Canon Formation: Recognizing Scripture, Not Inventing It

Skeptics often allege that the biblical canon was assembled centuries later by power-hungry bishops or Emperor Constantine. But canon formation was not an imposition—it was a recognition of what was already authoritative.

Wes Huff emphasizes that early Christians knew which books were apostolic and used in all the churches. By the second century, the core New Testament books—Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters—were widely accepted. The Muratorian Fragment (c. 170 A.D.) confirms this.

Old Testament books were similarly recognized. Jesus and the apostles consistently referred to the Law, Prophets, and Writings as authoritative Scripture (Luke 24:44).

By the fourth century, formal canon lists merely confirmed what had already been practiced in the churches for centuries.

Translation: From Greek and Hebrew to English

Once the original text is reconstructed, it must be translated. Translators of the English Standard Version (ESV), first published in 2001, used the Masoretic Text for the Old Testament (with reference to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint), and the Nestle-Aland 27th edition and United Bible Societies’ 4th edition for the New Testament.

The ESV is an essentially literal translation. This means it aims to be as close as possible to the original wording, maintaining the structure and semantics of the source languages while still reading naturally in English.

The translation committee of the ESV included over 100 scholars and advisors from conservative evangelical backgrounds, committed to both scholarly rigor and theological fidelity.

They operated not in secret, but in full view of academic and ecclesiastical communities, with footnotes explaining translational decisions and textual variants. This transparency is the opposite of how the telephone game works.

A Reliable, God-Preserved Word

The Bible we have today—especially in translations like the ESV—is not the product of distortion but of preservation. While human scribes did make mistakes, the sheer volume and geographic diversity of manuscripts allow us to detect and correct those errors with remarkable precision.

The telephone game analogy collapses under scrutiny for several reasons:

- It assumes oral-only transmission, whereas Scripture was written and copied.

- It assumes a single line, whereas the Bible was transmitted through multiple streams.

- It assumes no way to check the original, whereas scholars have tens of thousands of manuscripts.

- It assumes intentional or inevitable distortion, whereas careful copying and modern textual criticism enable us to reconstruct the originals with confidence.

As Daniel Wallace puts it, “We do not have the originals, but we have so many copies that we can be sure of what the originals said.”

Christians can be confident that when they open a faithful English Bible like the ESV, they are reading a translation of God’s inspired Word that has been providentially preserved across the ages. The process is not only historically defensible—it is also theologically reassuring, reflecting the sovereignty of the God who gave His Word and promised to preserve it (Isaiah 40:8; Matthew 24:35).

S.D.G.,.

Robert Sparkman

rob@christiannewsjunkie.com

RELATED CONTENT

Daniel Wallace, Wes Huff, Michael Kruger and Michael Horton discuss the telephone game analogy and the reliability of the transmission of the Bible in this video.

Concerning the Related Content section, I encourage everyone to evaluate the content carefully.

Some sources of information may reflect a libertarian and/or atheistic perspective. I may not agree with all of their opinions, but they offer some worthwhile comments on the topic under discussion.

Language used in the videos may be coarse. Coarse language does not reflect my personal standards.

Finally, those on the left often criticize my sources of information, which are primarily conservative and/or Christian. Truth is truth, regardless of how we feel about it. Leftists are largely led by their emotion rather than facts. It is no small wonder that they would criticize the sources that I provide. And, ultimately, my wordview is governed by Scripture. Many of my critics are not biblical Christians.

Feel free to offer your comments below. Respectful comments without expletives and personal attacks will be posted and I will respond to them.

Comments are closed after sixty days due to spamming issues from internet bots. You can always send me an email at rob@christiannewsjunkie.com if you want to comment on something, though.

I will continue to add items to the Related Content section as opportunities present themselves.